In my genealogic research of Sicilian

and Italian records, I have been able to trace many families back

through several generations, into the early 1700s and even earlier.

I have almost invariably found that there was at least one

'brick wall' in each of these families, where the line started with a

child for whom both parents were listed on the civil

registration of birth in Italian as 'padre ignoto'

and 'madre ignota' or 'genitori

ignoti' (father unknown, mother unknown, or parents

unknown). Another way it was expressed was to follow the

individual's name with the term "d'ignoti", e.g.

"Maria Esposta d'ignoti", meaning "Maria Esposta

of unknown [parents]".

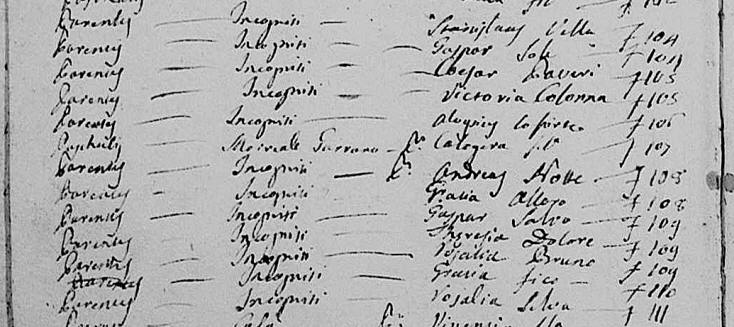

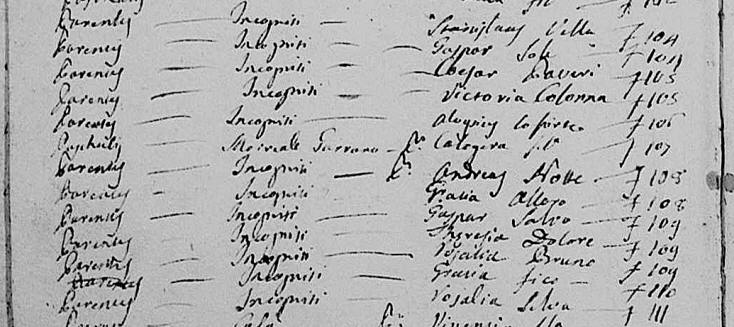

On earlier baptismal records, the parents of these children were

listed in Latin as 'genitoribus incogniti' or 'parentis

incogniti'. The

Italian and Latin terms mean the same thing. A more

pejorative term is used in some towns: 'padre incerto'

(father uncertain). Church records may also

describe foundlings as 'filius/filia universitatis'

(son/daughter of the community).

(Note: this page is about abandoned

children, whose parents are unknown. For a discussion

of orphans, whose parents are

known, but deceased, see

bit.ly/OrphansIllegitimatesFoundlings)

THE CAUSES: Infant abandonment was widespread,

for a variety of reasons. For one, unwed pregnancy was

a social disgrace, not only for the unwed mother but for her

entire family. Another obvious reason for abandonment was the extreme

poverty of most citizens of the 'Mezzogiorno', as

the southern Apennine peninsula and insular Sicily are known. And in some regions,

large complements of men, often far from home at sulfur,

salt, or potash mines brought high prostitution rates and subsequent

illegitimate births.

At least outwardly, church authorities were

zealous in protecting the identities of unwed mothers, and

saving 'face' for them and their families. A

more important motive was that the church considered

newborns as 'Turchi' (Turks) or heathens, who could

not be saved unless they were baptized. Sadly, its

concern for these children after baptism often was

not as great, once their souls were saved.

In addition to the church, civil officials were

also concerned with these cases because often the cost of the care of

such infants fell to the civil authorities. The

situation devolved to the point that many towns, both on

mainland Italy and the island of Sicily, installed a device

called 'la ruota (or rota) dei proietti': the wheel of the

castoffs, or 'the foundling wheel'. These wheels could

be in the outside walls of churches or convents, or in

larger cities, in the walls of foundling hospitals or

orphanages.

THE WHEEL: The wheel ('ruota' or 'rota';

in some places called the 'torno' or 'tornio') was a kind of 'lazy Susan'

that had a small platform on which a baby could be placed,

then rotated into the building, without anyone on the inside

seeing the person abandoning the child. That person

then pulled a cord on the outside of the building, causing

an internal bell or chimes to ring, alerting those inside

that an infant had been deposited. In the larger

towns, foundlings were baptized, then kept in a foundling

home with others, and fed by wet-nurses in the employ of the

home. There they may have stayed for several years

until they were taken by townspeople as menial servants or

laborers, or placed with a foster family. Or,

sadly but more likely, they never left the institution,

having died from malnutrition or from

diseases passed on by the wet-nurses.

In smaller towns, the foundling wheel may have

been in the wall of the residence of a local midwife.

She would have received the child, possibly suckled it

immediately to keep it alive, or arranged for a wet-nurse to

do so, then taken it to the church to be

baptized and to the town hall to be registered.

She then consigned a wet-nurse living in or near the town

to take the child and provide sustenance, for a monthly

stipend paid by the town. If the child was near death

when found, many midwives were authorized by the church to

baptize the infant, 'so that its soul would not be lost'.

Civil officials were often similarly authorized.

As bizarre

as the concept of the foundling wheel may seem to

some, the practice still exists to this day, in

countries around the world.

Instead of a wheel, unwanted children are placed in a

receptacle similar to a bank's 'night deposit box',

a called a 'baby hatch' or 'baby box'.

The article at the right was published by the Associated

Press on 13 February, 2023. |

|

Sometimes children were literally abandoned on

the street or on a doorstep, but the use of the foundling

wheel was so widespread that even these children were

often referred to as having been 'found in the wheel'. The

painting below, by Giaoacchino Toma, a 19th-century a artist

from Galatina, in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, is

entitled 'La

Guardia alla Ruota dei Trovatelli'

('The vigil at the foundling wheel').

Below is my interpretation of a story about

foundlings that was posted in Italian at the site

http://www.cognomix.it/

The Real Casa Santa

Annunziata [Royal Holy

Annunciation Home] of Naples was an

ancient institution devoted to the

reception of abandoned babies. It

was created in the fourteenth

century along with the "ruota

[wheel]", a kind of wooden

cylindrical drum where the children

were placed, then gathered inside by

nurses ready to intervene at every

call. The "wheel" was closed June

22, 1875, but infants were admitted

to the foundling home until 1980.

Residents of the institution were

called "sons of the Virgin,"

"Children of Nunziata" or "espositi

[exposed ones]", that is, exposed to the

protection of Our Lady. Hence the

surname Esposito, of which we

have the first written evidence in

the archives of the Royal House of

Naples [in what was then the Kingdom

of Sicily] with a "Fabritio Esposito,

age two years, cast off" at the

Annunziata on 1 January 1623 at

three-thirty AM.

This surname was used for all the

"abandoned" until 1814 when Joachim

Murat, the French general, brother

of Napoleon Bonaparte and finally

the King of mainland Sicily, eliminated the

practice. The surname Esposito is

still the most widespread in the

region of Campania. |

|

|

|

The wheel in which

foundlings were placed |

|

The surname Esposito, regarded

as a stigma, could no longer be

used: it was the duty of the civil

authorities, therefore, who recorded

the arrival of the children, having

to invent a surname every day.

The foundling home staff let themselves

be inspired by everyday life: if the

sun was shining, the orphans of that

day would be called Splendente

[Shining]; if someone knocked on the

door at the time of the first

abandonment of the day, the last name

would be Tocco "Tapping", and

so on.

The eminent sculptor and designer

Vincenzo Gemito was placed in the

wheel on 17 July, 1852 (the day

after his birth), and was given the

surname Genito ("that which

is generated, a son"), which later,

due to an error in transcription,

became Gemito. |

|

http://www.cognomix.it/

paraphrased the above from an October 2013 article in

il Mattino which says:

"That name, 'Esposito', which tells the

child's origin, was considered a stigma, which made life

impossible for people who grew up at the Annunziata."

Il Mattino adds: "The foundling

wheel was created to accommodate only babies, but desperate

mothers also left older children, sprinkling them with oil

to allow them to fit into the mechanism. Too often, that

passage caused fractures and internal injuries; so to

prevent abandonment of older children, the space to lay the

children was reduced from a hand's-width to three quarters

of a hand's-width."

THE RECORDS: Throughout Europe, church records, dating in some

towns from 1540, were kept of all baptisms, even those of

foundlings. Generally, church records didn't even give

any surname for a foundlings, just a 'given name' and the

notation 'parentibus ignoti' as in 'Phillipus

parentibus ignoti' (Filippo, unknown parents). Such

children went through life with only a first name and the

handle 'foundling'. Often they simply adopted a

nickname or descriptive surname to distinguish themselves

from other 'Filippo's'.

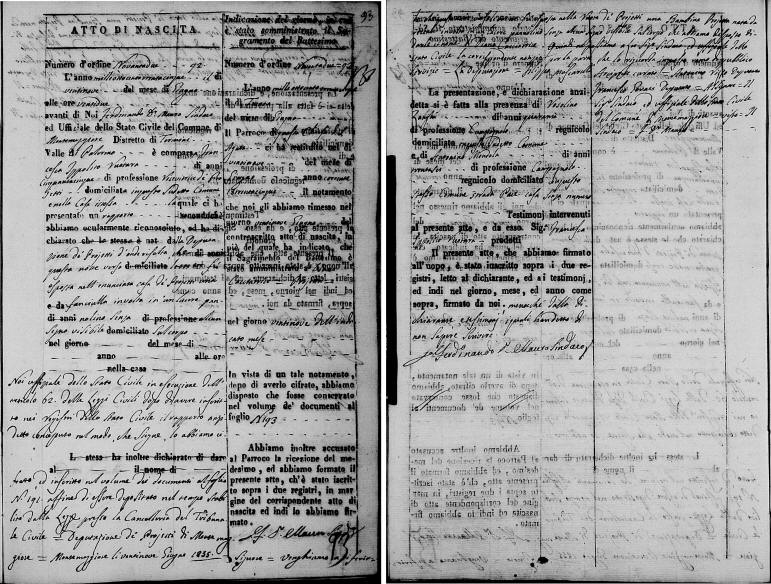

From about 1809 - 1820, influenced by

Napoleon's 'civil code', civil records of

birth were instituted

in northern Apennine duchies and principalities like Venice

and Genoa and in the Kingdom of Sicily stretching from Abruzzo and Napoli on the mainland to Messina and Palermo on

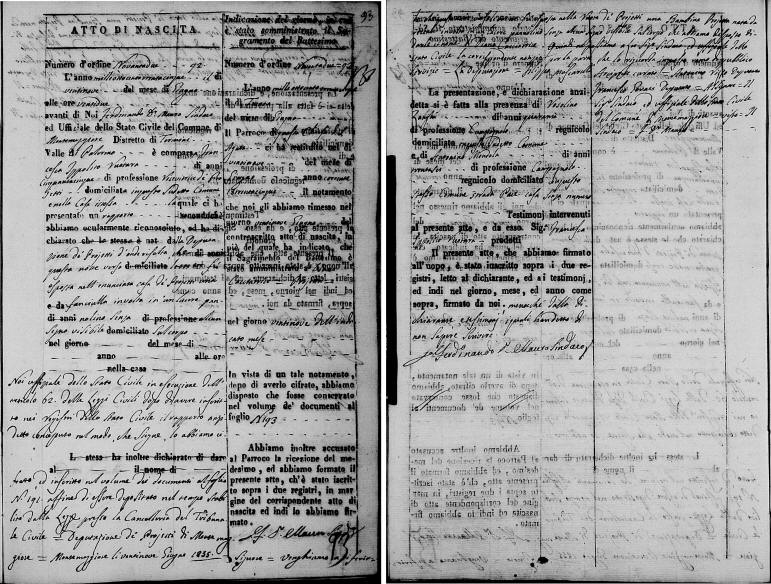

insular Sicily. From that time, not only were

foundlings' baptisms recorded at churches, but each child was

civilly registered by the town's 'Uffiziale dello Stato

Civile', the Official of Civil Status, in the civil

'Atti di Nascita', or Records of Birth. For

ordinary births,

such records gave the date; names and occupations of the

parents; and the name of the child. In the usual case, there

was no other description of the child, besides its gender.

Civil birth records for foundlings were

different. The 'dichiarante', or declarant (the

person presenting the child, in ordinary cases its father) was

identified by a title, which varied by town. In many,

as in Serradifalco, on the island of Sicily, the title was 'ricevitrice dei

proietti', 'receiver of castoffs'. In other towns, like Sora on the mainland, it was 'custode della

ruota dei proietti', or 'keeper of the wheel of the

castoffs'. But the most poignant, to me, was the simple

term used in the Sicilian village of Racalmuto, namely 'ruotaia':

'wheel-lady', or 'lady of the wheel'. In other towns

variations such as 'rotaia' or 'rotara' were

used, with the

same meaning.

Note: Often, "proietto"

and "ruotaia" are written as "projetto" and

"ruotaja". The letter that looks like the English

letter "j" is not a "j" at all, but the letter "i" with a

long tail. It was often written that way when it

appears between two other vowels, and it is pronounced the

same way as "y" is pronounced in English: hence "pro-YETT-oh"

and "ruoh-TY-uh". The "i with a tail"

often appears in other words and proper names, such as "calzolajo"

(shoemaker), Ajello, Saja, and so on. The

Italian word "progetto" meaning "project", as in a building

project, is pronounced "pro-JETT-oh" (where the "g"

sounds like the English "j"!) and has a completely different

meaning.

Rather than simply giving the child's

gender, the civil registration document of a foundling usually

stated where it was found: 'nella ruota pubblica in

questa comune' ~ 'in the public wheel of this town'; or

if appropriate, on whatever street or doorstep it was found.

If the child had evident birthmarks (or none), that fact was

noted, along with a description of the clothing or any

'tokens' found on the baby. Some records stated that

the midwife had arranged to initially feed the child and

that it had then been consigned, according to law, to a 'nutrice',

a wet-nurse; sometimes the name of the wet-nurse was given.

From the early 1800s until 1865, civil records were kept on

pre-printed forms in a format originally specified by the

Napoleonic Code. The extra information

recorded for foundlings did not fit in the blanks, so often

the written information did not fit the preprinted category.

In some cases, the information was 'squeezed' into the

preprinted form, but frequently the civil

Register of Births had a 'Parte Seconda' (Part 2) and the

foundlings were registered in that section, filed after

the main portion (Part 1) of the register. These Part

2 foundling records were completely handwritten. Other

non-standard births (e.g. late announcements) might also be

filed in Part 2.

In

some towns, including Palermo and Catania, there was a

complete separate register for foundling births, In some

larger cities, all foundlings were abandoned at, or brought

by their discoverers to, an ospedale, orfanotrofio,

or brefatrofio (foundling home), which prepared

its own records and also submitted the information to civil

authorities to be registered. The

earliest civil records followed the church's policy of

simply giving foundlings first names, with the suffix

'foundling', later, they would give a concocted surname

followed by 'foundling', as 'Filippo Faccilorda, esposto'.

Civil records after 1865 gave only a made-up first name and

surname, but the body of the record itself clearly indicated

that the child was a foundling.

In some locales and eras, the abandonment of children

by their unwed mothers was essentially imposed by

civil and church authorities. Town priests and

midwives closely scrutinized young single women, and if they

discovered a pregnancy, the expectant mother was 'encouraged' to give

the child up, to avoid familial disgrace, and, more

importantly to the church, to assure that the infant was

baptized before it died. Though the use of the wheel

was nominally secret, many institutions required alms or

payment by the mothers, so there was a 'paper trail' of

evidence even though the general public was supposedly

unaware of the particulars. If a mother was unable to

pay alms, often she was required to work for free in the

institution as a wet-nurse.

Such activities could not long be kept secret

from the community, and although the names of foundlings'

parents were not officially recorded, no doubt in small

communities the true relationships were known. In some

cases, a mother would volunteer to take her own child to her

home to wet-nurse, though 'officially' the infant's parents

were unknown.

Unless an abandoned child's parentage was officially

established at some later date, most commonly by a

rectification (specifically, a "legittimazione" or

"legitimization") that was filed to give the names of one or

both parents, or on the post-birth marriage record of

its parents, the child was always officially referred to by

its imposed name and as the child of unknown parents.

When such a child married, even though he and everyone in

the community might have known who his parents were, if no official

correction had been made, his marriage record would list his

parents as 'genitori ignoti'.

Some children may have been abandoned because their

parents were unmarried, or married in church ceremonies not

recognized by civil authorities. If the couple was later

married in a civil ceremony, the names of the children they

had abandoned and their birth dates would be stated in the

couple's civil marriage record, thus acknowledging and

'legitimizing' the former foundlings.

Like those of all citizens, foundlings' birth,

marriage, or death records, or rectifications, are kept

permanently in the Anagrafe or Registry Office of

each town, with a copy in provincial or tribunal archives.

These records may be searched in person, or in many cases

viewed on microfilm produced by the Mormon church, or

on-line at genealogy sites. Records of the disposition

of abandoned children to wet-nurses or to foster homes may

exist, but they are less easily uncovered and usually

require on-site research at the towns, churches, or

provinces involved.

These original birth records often reflect the large

proportion of foundling births in a town. In Racalmuto,

for example, in the year 1880, there were five hundred and

twenty four legitimate births recorded, and

eighty-three infants left in the wheel, a staggering

fourteen percent of all births! Other years, and

other towns, show similar statistics. For example, the

index of baptisms of the Mussomeli church records for the

years 1831 through 1845 lists baptisms alphabetically by the

first name of the infant's father. There are several

pages of names beginning with "P", dozens of them reading

'Parentis Incogniti' ~ 'parents unknown'.

In some cases

infants were not

actually left somewhere, but

were reported by a midwife as having been delivered by her, from "una donna che non

consente essere nominata" - "a woman who does not

consent to be named", and neither was a father named.

In these cases, even though the midwife obviously knew the

identity of the mother, she was officially unknown, as was

the infant's father.

'FOUNDLING' (trovatello) versus 'ABANDONED CHILD' (abbandonato): There

is a tendency to use these two terms to mean the same thing.

There can be a difference, however.

Clearly, infants who were found

in 'the wheel', on a doorstep, in the woods, or in the

middle of the road were abandoned before they

were found.

But there

is another class of abandoned children, as noted above;

those who were delivered by a midwife to an unnamed woman who would

not or could not name the child's father. In these

cases, the mother of the child abandoned the child to the

midwife and hence to the local authorities. She was

known only to the midwife, not reported in the record of

birth, so she was 'officially' unknown, as was the father.

Hence, while all foundlings were abandoned

children, not all abandoned children were strictly

foundlings.

In its effect on the future of the infant,

the results were the same, whether the child was abandoned

to the wheel or abandoned to a midwife. While not

strictly 'found', the latter, just as for an actual

'foundling', was given a concocted name, consigned to a

wet-nurse or home for abandoned children, and future

official references to his parents would list both of them

as unknown. See the case study for

Santa Venerdi Proietta, below.

If an unwed woman was named in her

child's record of birth, but she did not name its father, it

would then bear her surname, as an illegitimate

child, but not a foundling.

NAMES: Although their parents were at least

'officially' unknown,

foundlings had to be given some kind of name, and this was

done by the receiver of foundlings, or the priest baptizing

the child, or the civil official registering the event.

On an ordinary birth or baptism record, usually only the

given ('first') name of the baby was recorded, since its

surname was the same as its father's. But with

foundlings, the given and the surname were recorded.

Both, of course, were 'made-up', and in the earliest

records, first names were recorded, followed by a word

that was synonymous with 'foundling', as in Pietro

proietto.

'Proietto' meant

'castoff' or 'thrown away' in early Italian, and consideration of

the word's Latin origin sheds some light on the way

foundlings were looked upon. The origin of 'proietto'

was the Latin 'proiectus' (written 'projectus' in

cursive), and early church baptisms

used 'Projectus' as a surname for foundlings.

One meaning of 'proiectus' was 'cast' or 'thrown'. But

Latin dictionaries give secondary meanings: 'lowlife';

'miserable'; 'deplorable'; 'honorless'; 'lamentable'; and

many more similar meanings. Such was the view

they had of these parentless infants.

Other surnames clearly

meaning 'foundling' or 'abandoned' include Trovato (found),

Abbandonata (abandoned), or

Esposto/Esposito (exposed). In the

various duchies, principalities and other states on the

mainland, at baptism, frequently a foundling was given a saint's name or

other made-up name as a first name, then a surname that was

the Latin possessive form of the same name, for example Genesius

Genesi (Genesius, son of Genesius) or Amatus

Amati

(Amatus, son of Amatus). Such 'first' or given

names were then Italianized in the civil records, resulting

in Genesio for Genesius; Amato for Amatus, etc.

Sometimes a foundling listed by only its first name and

followed by "d'ignoti" eventually had the descriptive

term capitalized and evolved into a surname, D'ignoti

or Dignoti.

In Roma, where a foundling's mother was

often listed as "m. ignota" (madre ignota, mother

unknown), a pejorative term was "figlio di Mignotta!"

that is, "Son of an unknown mother!" Since most foundlings

were illegitimate, that was a 'polite' way of calling

someone a bastard.

Note: On the death record of a foundling, their

parents' names were invariably listed as padre ignoto

and madre ignoto, or the foundlings were referred to

as d'ignoti. These terms did not mean that the

parents' names were simply unknown to the clerk or

declarants of a record, they meant that the person was

a foundling. If it was intended to convey that

the person was not a foundling, but their parents were not

known to anyone in the proceeding, in the place for the

parents' names, the clerk would enter "s'ignorano"

(the names are not known to us).

The descriptive 'foundling surname'

eventually became the person's official surname.

When a foundling boy grew up, married and had

children, the

children's surnames would be the same as their father's even

though they themselves were not foundlings. Many of

these surnames exist to this day, with their bearers having

no idea that somewhere in their ancestry there was a

foundling child.

Even the given names of foundlings were

often unusual or fantastic, like Cleopatra or

Romulo. When surnames other than Proietto,

etc. began to be used, they, too were unusual and often

stigmatic, like Urbino

(blind); lo Guasto (crippled);

Milingiana (eggplant); and Vinagro

(bitter wine). A child with such a name was marked

throughout his or her life as one with 'genitori ignoti'

(unknown parents) and

by inference, as a love child, although at least in theory,

it wasn't known whether or not the child was abandoned by a married

woman who conceived it in wedlock. Even children with

less insulting surnames were thusly scorned. Di Dio

(of god); D'Angelo (of an angel); del Popolo

(of the people); degli Uomini

(of the men); di Giugno

(born in June) and Gelsomino (jasmine) are all mild

enough surnames, but in certain towns they were used

exclusively for foundlings, and marked them just as surely

as the cruder versions.

Below is a poignant example of a name given to a child found

in the town of Montemaggiore Belsito on the

morning of 29 June 1835, in the public wheel of the 'House

of Castoffs'. She was found and presented by the

Ruotara (female wheel-keeper) Francesca Ippolito, age

29. The infant was a girl, wrapped in ragged digapers,

without any birthmark or token, and was given the name

Diana, and the surname Cacciatrice.

In Italian, the word "cacciatore" signifies "hunter"; the

feminine form is "cacciatrice", meaning 'female hunter", or

"huntress". So a flippant official gave the

unfortunate child the name "Diana the Huntress",

possibly to show off his knowledge of Roman mythology.

Regardless, it would be recognized by one and all

as a "foundling name", and the girl would bear that stigma

all her life.

Eventually, laws were passed

prohibiting the stigmatic names, but in small towns, because

the names were made up, they were invariably different than

the surnames usually occurring there. Often such names

carried a 'foreign' implication: Lopez,

Romagnoli, Suez and even Miller

have appeared as surnames in Sicilian birth records.

These may be valid names, derived from ancestral

ethnicities, or they may have been names concocted for

foundlings. The surname Miller, for example,

may have been given to a foundling because the midwife,

receiver of foundlings or civil official knew

(without officially revealing it) that the infant's father

was an Englishman named Miller; or assumed that to be

the case; or simply chose Miller to show that

the child was 'not from here, not legitimate'.

Coniglio

is a perfectly valid Italian/Sicilian surname, but in a town

of only 1,500 souls, where no one else had the surname

Coniglio, any child with that name was obviously a

foundling. In some cases, a foundling was simply

given the name of his village as a surname: thus,

Giuseppe Vallelunga, Rosa Siragusa, etc.

However, it was more common to give foundlings the name of

some other town, or a modification of a town

name to indicate 'from the town', such as Barese,

Palermitano, Tirminisi, etc.

This also marked the child as a

'stranger' or the child of a stranger. Place names as

surnames, I believe, were more common as foundling names

than they were as places of origin. For a more detailed analysis of

Sicilian town place-names as surnames, click

HERE.

|

Typical Foundling Surnames and Towns in

Which They Were Prevalent |

|

|

SURNAME |

MEANING |

TOWN |

|

Abbandonata |

abandoned |

Sora (Frosinone) |

|

Asinello |

little ass |

Mussomeli

(Caltanissetta) |

|

Cagnazzi |

bitches |

Santeramo (Bari) |

|

di Dio |

[child] of

God |

Castrogiovanni

(now Enna, Enna)

San Piero Patti

(Messina)

Valguarnera Caropepe

(Enna) |

Esposto,

Esposito |

exposed |

Serradifalco

(Caltanissetta)

numerous others |

|

Gelsomino |

jasmine flower |

Montemaggiore Belsito

(Palermo)

Mussomeli |

|

Giumento |

mare |

San Cataldo

(Caltanissetta)

Serradifalco |

|

Milingiana |

eggplant |

Serradifalco |

|

Miller |

[yes, Miller] |

Serradifalco |

|

del Popolo |

[child] of the people |

Castiglione (Catania)

Montalbano di Elicona (Messina)

Linguaglossa (Catania) |

|

Pampinella |

leaflet, sprig |

Altavilla

(Palermo)

Baucina (Palermo)

Santa Flavia (Palermo) |

|

Portoghese |

Portuguese |

Trapani (Trapani) |

|

Proietto |

castoff |

Racalmuto (Agrigento) |

|

Spavento |

fright |

Mussomeli |

|

Spurio |

spurious |

Mussomeli |

|

Trovatello |

little foundling |

Sant'Angelo Brolo

(Messina) |

|

Trovato |

foundling |

Acireale

(Messina)

Alcamo (Trapani)

Valguarnera (Enna)

numerous others |

|

Tulipano |

tulip |

Mussomeli |

| |

|

|

ALIASES: While

abandonment of children born out of wedlock was sanctioned

by both Church and State, it was illegal for a married

couple to abandon a child. Though there were some

cases in which legal parents saw no other recourse, the

overwhelming majority of foundlings were illegitimate

children, to the extent that the word 'foundling' or any of

its variations was synonymous with 'illegitimate'.

If you were a foundling, you were a bastard child,

considered by society the lowest of the lowest social class.

Because of such stigma, on reaching

adulthood, many foundlings took less stigmatic surnames

rather than Proietto, Esposito, or the formulaic, contrived,

and unique surnames that had been concocted for them.

These self-chosen names were usually simply common surnames

in their villages, not necessarily with any familial

connection. In some cases the new names were legally granted

by the judicial system, but in many instances, the foundling

simply 'went by' a name of their choosing, to the extent

that after being used for some time, it essentially became

their name. Such persons often had both names

recorded, for example, as follows: Giuseppe del Popolo,

inteso Marconi, that

is, 'Giuseppe del Popolo, going

by Marconi'; or Ciro Gelsomino,

detto Faso (Ciro

Gelsomino, called

Faso); or Paolo Proietto, alias

Burgio ('alias'

has the same meaning in Latin, Italian, or English).

When foundlings emigrated, many

immediately changed or modified their names and/or revised

their family stories, claiming to be orphans, or 'love

children' of important figures, nobles, or officials, or

having living legitimate parents left behind, since often

there was no one in their new surroundings who could refute

their claims. See an example in the case study for the

Famiglia Messina.

THE FATE OF FOUNDLINGS: Civil records were and are

open to the public, in 'registri' or registers. Citizens could go to the town hall and ask to see them.

'Unknown' parents of a foundling could therefore see what

name had been given to their child (from the date and the description of

tokens or clothing), and sometimes, to whom the baby had

been consigned. They might then reclaim the child,

although recorded instances of this are few. If a

legally married couple reclaimed a child, they would then go

to the civil authorities for registration of a 'legittimazione',

a correction which would officially name them as parents,

and legitimize the child's birth. Tales are also told

of many a mother who claimed her child without revealing

their relationship, being paid a stipend to wet-nurse her

own child.

In the foundling homes, hospitals or asylums of large

cities, many babies suffered horrific conditions.

Wet-nurses were often of lower classes and carried diseases

passed on to the babies. Children who survived to

early childhood could be 'farmed out' as servants,

field laborers, or worse: often, boys were indentured or

sold to sulfur mine owners or workers as 'carusi'

(mine-boys) to carry raw sulfur out of the mine; and girls

were often sold into prostitution.

These horrendous possibilities, of course didn't preclude the

consignment of foundlings to foster-families that did care for

them responsibly, and raised them to adulthood. Because

of the nature of these arrangements, easily available public

records are hard to come by. At one point in Italy's

history, foundling homes became so crowded, and the total

pay required for the wet-nurses of its inmates so high, that

civil authorities hired 'external wet-nurses' to care for

some infants away from the institutions. They even

sometimes acknowledged unwed mothers and paid them a sort of

child support stipend, to nurse their own children.

This led to some bizarre situations.

In the years following the unification of Sicily with

northern Apennine states (the 'resorgimento'), vast church property was appropriated by the

state, and church and state were at odds. Marriages

that took place solely in church were not recognized by the

civil authorities, and in order for a union (and its

offspring) to be legal, a couple was required to be married

in a civil ceremony, usually at the town hall by a public

official. When the policy of civil stipends to unwed

mothers was instituted, sometimes an expectant mother would

marry in church, avoiding family disgrace, but would not

take the civil vows. This made her child

illegitimate in the eyes of the state, entitling her to

a stipend!

In small towns, the fate of foundlings may

have been somewhat better than in it was in large cities. In smaller communities,

they may not have been subjected to the

crowding of orphanages, but instead were consigned to the individual

families of the wet-nurses. There, though they may

have eventually been required to work in the fields or the family

business, the same as the family's natural children, they

may also have found some measure of acceptance and

normality. However, their names marked them as

foundlings. In a class-conscious society, sons of

landowners married daughters of landowners, daughters of

tradesmen married sons of tradesmen, and foundlings married

foundlings.

IDENTIFYING

FOUNDLINGS' PARENTS:

As

family researchers try to 'build' their family trees further

and further back, many are frustrated by the 'brick wall'

presented by a foundling ancestor. Unfortunately,

exactly because foundlings were intentionally

abandoned by unknown parents, it is virtually impossible to

determine the names of their biological parents. In

many cases, it isn't even possible to determine the names of

the families that raised them.

As early as the 1500's, churches kept

records of baptisms for all children, including those for

whom only one parent was known as well as for foundlings.

In the 1800's, civil registrations of births began to be

recorded. So there can be some clues in foundlings'

birth and baptism records. Civil records give the name

of the receiver of foundlings or the midwife who presented

the child for registration, along with the names of two

witnesses to the registration, and often the name of the

wet-nurse or institution to which the child was consigned.

It's possible that one of those named belonged to a family

that raised the child. Baptism records give the

names of the foundlings' godparents; again, possible foster

parents of the infant.

However, remember that the parents of a

foundling were unknown for a reason: the anonymous

abandonment of children was sanctioned by church and state

to protect the 'honor' and therefore the anonymity of unwed

mothers and their love partners. Even in the rare

cases in which official consignment, fostering or adoption

documents were created, THE BIOLOGICAL PARENTS OF THE

FOUNDLING WOULD NOT BE NAMED in such documents.

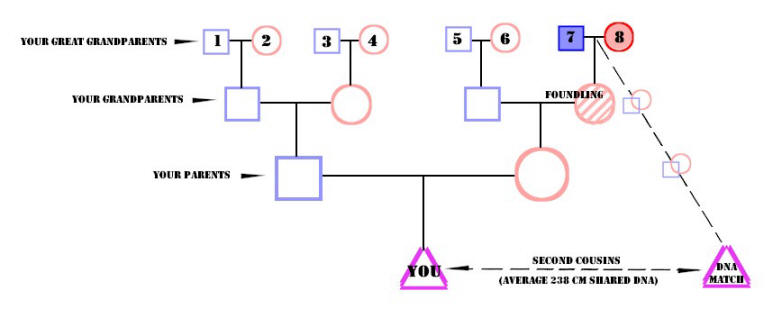

With the recent trend towards DNA testing,

it's possible that descendants of relatively recent

foundlings may be able to locate close relatives who can

help to clarify their lineage, but the farther back the

'brick wall' occurred, the less likely that even DNA methods

can help.

Briefly, DNA venues test your DNA,

then compare it to others who have tested, and provide a

list of persons, some of whose DNA matches some of yours.

DNA is measured in centiMorgans, or cM, and the more

cM you share with a "DNA match", the closer your

relationship. If these "DNA matches" have family

trees and are willing to share information with you, you may

find that they have ancestors in common with you. This

may help you to determine the identity, or at least the

close family of the parent or parents of your foundling

ancestor.

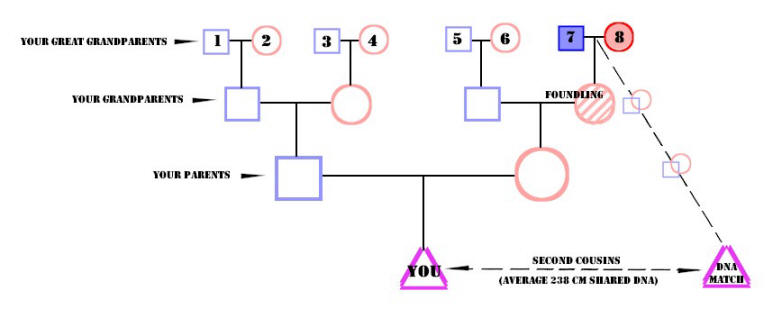

For example, say one of your grandparents

was a foundling. That would mean that two of

your eight great grandparents were unknown. We share

great grandparents with our second cousins, however, not

every second cousin is descended from the unknown couple.

To isolate one or both members of the couple, you would

first have to develop your own 'pedigree' or family tree

that identified the six great-grandparents who were NOT the

foundling's parents. Then if you could analyze

the trees of all the second cousin "DNA matches" that you

have, you might be able to determine those who were

descended from your known ancestors. By elimination,

any second cousins who were not descended from your known

ancestors must be descended from one or both of the

foundling's parents, so one or both of those second cousins'

great grandparents are your ancestor(s).

Second cousins, on average, share 238 cM of DNA (actually,

from 43 cM to 504 cM), so you'd have to study your DNA

matches in that range and hope they have trees back to their

great grandparents. In the diagram, great grandparents 7 and

8 are the unknown parents of the foundling, and obviously

would have different names than your known great

grandparents.

The same logic could be applied if your foundling ancestor

was your great grandparent, but in that case, its unknown

parents would be your great-great grandparents, of which you

have sixteen. So you'd have to know fourteen of

the sixteen, and find enough DNA matches who are third

cousins who had trees that could allow the same process of

elimination.

Needless to say, that would be a Herculean task, not likely

to be successful. In general, we usually have to resign

ourselves to the fact that we'll probably never know our foundling

ancestors' true parents.

ADOPTION RECORDS: I have found no official

records pertaining to the formal 'adoption' of foundlings.

In most Sicilian and Italian towns, from early on through

the early nineteen hundreds, adoption was not common and

even illegal, and the only formal adoptions allowed were

those of orphans, that is, children whose parents were

known, but one or both of whom died before the child reached

adulthood.

Adoption of foundlings, whose parents were unknown, was

generally not permitted. Foundlings may have

lived out their lives in a foundling home, or in private

homes as menial servants, or worse; they may have been

consigned to families as persons who worked in exchange for

room and board, or to owners of the quarries or mines in

which they toiled. Even though foundlings' parents

were officially 'unknown', a relative of the foundling, an

aunt, mother or sister of the 'disgraced' true mother, may

have raised the child.

In some cases, they were formally consigned to

official guardians, whose families became the foundling's

foster family. One case of foster parenting can be seen in the case study of Genesio

Genesi, linked below. Even

where there are official consignment papers,

since the foundlings' parents were unknown, that is how the

parents

were listed. No names of birth parents are given in

such papers.

There generally are no official records of any of

these dispositions, however in certain instances couples who

had abandoned children born to them prior to having been

married in a civil ceremony may have later married civilly,

and in their marriage record declared the names of the

children and acknowledged them as their own. For more

detail, click

HERE.

In cities or larger towns, a

child may have been 'farmed out' (even for pay to the

institution): boys as 'carusi'

or child mine workers; girls as servants, or, sadly, as

prostitutes. In many cases, in small towns, these infants

were raised in the families of the wet-nurse to whom they

were consigned, or families which needed an extra set of

hands for field work or other family enterprises.

LEGENDS: A very common explanation many

families were given about a foundling ancestor is a

variation on the following theme: A young girl was working as a

servant in the home of the local prince (or rich

businessman, or priest). She was impregnated by the

man (or his son, etc.), who could or would not marry her, and she left the

baby, of noble or upper-class blood, in the wheel.

Some of those stories may carry a grain of truth;

however, there is usually no way to corroborate them, and I

believe the great majority were fiction, made up to assuage

the shame of families with unwed daughters who had become

pregnant. Hopefully, today the world is less

judgmental.

|

|

The above material is a

synopsis of information from my own research of

Sicilian and Italian birth, marriage and death

records, augmented by correspondence with

genealogist Ann Tatangelo (angelresearch.wordpress.com),

and by the description of foundling management

in the book

Sacrificed for Honor, by David I.

Kertzer. |

|

|

|

I've been

privileged to be asked to do foundling research for Henry

Louis Gates' PBS series 'Finding Your Roots'.

|

|

I've

contributed to three episodes so far, two with research on

the ancestors of Marisa Tomei, and one future episode that

deals with the heritage of a (presently undisclosed)

Hollywood actor. Click the image below to view the

recent show involving Marisa Tomei. |

|

|

|