Ange Coniglio's GenealogyColumns

|

|

. |

|

Click on a title to jump to that column. |

|

|

|

. |

|

Finding Your

Immigrant Ancestors© A fellow writer recently expounded on his lack of interest in the origins of his European ancestry. He engagingly wrote ‘None of my ancestors ever looked back with anything like nostalgia. As far as they were concerned, it was "good riddance" to the Old Country and the quaint customs of impressments, bonded servitude and nothing to eat.’ He wrote that ‘now, several generations removed from the terror of it, I still have no desire to seek my roots’ and he finds ‘secret satisfaction in being the descendant of refugees who were nobodies.’ I share some of those feelings, but I must address a widespread misconception that genealogy is of little use unless it results in the knowledge that one’s ancestors were rich, or noble, or famous, or all three. If finding ‘famous ancestors’ is your sole reason for doing genealogical research, you are likely to be disappointed. The great preponderance of souls who have inhabited this earth have been neither ‘members of the U. S. Senate, nor generals on horseback, nor millionaire entrepreneurs,’ so don’t be surprised if you find none in your family tree. Ancestral ‘celebrity searches’ can have an undesired effect. As a novice researcher, you may go on-line and find ‘trees’, posted by others that purport not only to show your ancestors, but that one or more of your ancestral lines descends from a prince, a famous author, or other luminary. You must ‘do your homework’ and corroborate each connection to the princely supposed ancestor, by confirming the sources of the information. If you don’t, the presumed connection to glory is worthless. I was the ninth and last child of Sicilian immigrants who came to America one hundred years ago. My father was a laborer, my mother a housewife (what else would she be, with nine kids?) I didn’t know it as a child, but my historical and genealogic studies have shown me that they lived in an impoverished land where the ruling classes excluded the common folk from education. To survive, they had to work at backbreaking labor in the fields or the sulfur mines. Their rights were virtually nonexistent. Women married as young as thirteen, to bear children every two years until their mid-forties, or later. If a woman’s husband died young, she immediately had to remarry, to provide a father for her children; then she commenced having a child every other year with her second husband. So, what had I to gain from researching the escapees from such a wretched life? I gained the knowledge that my ancestors, and my wife’s as well, trace back to mid-1700s Sicily. That my Coniglio ancestors back to my great-great-great-great grandfather were born in tiny Serradifalco (The Mountain of the Hawk), dead center in the island of Sicily. I found that Gaetano Coniglio was not only the name of my eldest brother, but of four of my direct ancestors. I learned that my father had more than the one brother that I had known of, and that ‘Pa’, like I, was a seventh son. I learned that my father, and his father before him, worked in the fetid sulfur mines from before dawn ‘til after dusk. And that as the near-caste system required, my father married the daughter of a sulfur miner. My investigations revealed that on my mother’s side, one ancestor was an abandoned child, left in the town’s ‘foundling wheel’, who beat the overwhelming odds for such children and survived to marry, and to generate over six hundred descendants (that I know of). I learned that none of the hundred and twenty direct ancestors I have identified, before my own parents, could read or write. So, even though my ancestors were ‘nobodies’, I’m glad to have found out about them and their lives. I feel that not only their genes, but their experiences as well, have shaped me and my living relatives into what we are today. I’m proud of their perseverance, and the fact that my family, which descended from such simple folk, continues to emulate their examples of strength and resolve. |

|

. |

|

Finding

Your Immigrant Ancestors© Four Keys Friends and relatives who know that I have been researching my family genealogy for years often ask me “Are you finished yet?” Since I, like everyone, had two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, sixteen great-great-grandparents, and so on, it’s unlikely that I’ll ever be finished! Even filling in information about known relatives sometimes takes time. Sometimes we are treated with unexpected, previously unknown or forgotten facts about our closest relatives. For example, I knew that my family settled for a time in Robertsdale, PA. Three brothers were born there, including Felice, born in 1920. And I knew that in 1923, my sister Carmela was born in Buffalo. But I didn’t know exactly when the family moved to Buffalo, nor where they lived in the 1920s. My surviving siblings were too young at the time, and can’t remember those details. Then, very recently, I was searching for my father’s naturalization records, and visited the Erie County Clerk’s office on Franklin Street in downtown Buffalo. There, in the basement, are alphabetized index cards of persons naturalized from about 1820 through about 1929. The index cards give the naturalization date, as well as references to a microfilm record of the original papers, which may be read and copied ($1 per copy). My father’s papers included affidavits from friends in Robertsdale, who stated that they had known him until he left there in 1921, filling in one part of the puzzle. The papers also showed his Buffalo address, and that of my mother and five siblings, as 18 Peacock Street. Another question answered! Further, other archives at the office include old street maps of Buffalo, and on a future visit, I plan to look for the long-gone Peacock Street, part of the infamous Dante Place canal district and “the Hooks”. If you're researching ancestors, begin with the earliest relative about whom you know the following:

Local records like censuses or death records may help find this information. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormon Church) has Family History Centers (FHC) associated with almost every one of their churches (three in the Buffalo area); with resources and volunteers to help you find local records (some at their Centers, some at other local institutions). Once you know the three items, use on-line resources to try to find immigration information. This may be available on free sites like www.ellisisland.org, or www.castlegarden.org/, or on the paid site www.ancestry.com. If you find your ancestor's immigration record, it may give more information about him/her that you weren't aware of. For foreign birth records or other vital statistics, once you’re reasonably sure of the "big four" items, and have possibly confirmed them from immigration records, the FHC can help you to find possible records of your relatives in the Mormon data base. They have extensive microfilms/fiches from thousands of towns around the world (regardless of the religion of the persons recorded). These film numbers may be found on-line from FHC computers, or from your home computer, once you know the process. They don’t show actual data, but which films and data are available for the time and place you are interested in. There may be none available, or there may be civil or church records of births, baptisms, marriages, and deaths. Once a film is identified, it can be ordered from Salt Lake City (through the FHC) for $5.50, entitling you to view the film at the FHC for one month. Films usually take one or two weeks to arrive, and can be renewed periodically. If you are lucky enough to find your ancestor's birth record, it will of course give the parents' names (and sometimes ages), from which you may be able to order another film, and go further back in history, etc., etc. Regardless of what new information you may find, I urge you to speak about your heritage to your descendants, etc., so that your knowledge will be preserved for posterity. Other than rental and copying costs, the Church makes no other demands. You can use the services regardless of your background or religion, and no proselytizing is done. Sometimes an immigrants passenger ship manifest shows information that can help in the search for original records. Ellis Island received immigrants from the late 1800's through the 1920's, and those records may be researched at the free site www.ellisisland.org Before Ellis Island, a major port of arrival to the US was Castle Garden. You can search for arrivals at http://www.castlegarden.org/ Also, the pay site www.Ancestry.com has many passenger arrivals for ports other than Ellis Island. If you're not an Ancestry.com subscriber, many public libraries and Mormon Family History Centers have computers on which you can access Ancestry.com (some facilities have access to more services than others). By going to http://bit.ly/LocateFSCs you can find your nearest Mormon Family History Centers, sometimes also referred to as FamilySearch Centers. Another reference that may identify origins is the US Naturalization system. There are many different types of “naturalization papers”, some issued by local courts, some by county courts, and some by federal courts. The records may be retained at those courts, or at local county vital statistics offices. A typical US Department of Labor Naturalization Service “Petition for Naturalization” shows the applicant’s date and place of birth, and date and place of departure. This is also true of same Service’s “Declaration of Intention”. Depending on the year and place of naturalization, you may be able to find these documents at one of the venues mentioned above.

Genealogy tip:

In many countries of Europe, women went by their “maiden” or birth names for

their entire lives, even after marriage. Thus, for example, Angela Alessi

was Angela Alessi for life, even after she married Giuseppe Coniglio. If

her name was shown on an Ellis Island passenger manifest, it would be as

Angela Alessi, and any accompanying offspring would be listed with their

last name as Coniglio. If she returned to Sicily and died there, her death

notice would be filed alphabetically under “A”’, and she’d be listed as

“Angela Alessi, wife of Giuseppe Coniglio.” |

|

. |

|

The Search for our

Ancestry In about one year, Americans will find in their mail a computer-readable form to be filled out for the nation’s twenty-third decennial census. As noted here previously, the U.S Census is an important resource for tracing one’s heritage, both in America and in finding records of ancestors from other lands. The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration states: ‘The Constitution of the United States (Article 1, section 2) mandates that an "actual Enumeration" of the nation's population be made at least every ten years so that "representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers." The inclusion of a recurring census in the Constitution marked the first time that a nation made an enumeration the basis of representative government. In essence, the census connects the American people to their government.’ For a modern census, a standard ‘short form’ is sent to most homes, for the head of household to fill out and return. A percentage of homes randomly receive ‘long forms’ with more detail about the lives of the residents. These longer censuses are then statistically analyzed to project estimates for the entire nation. Residency information affects the extent of Congressional districts, taxes, and other public concerns. The first census was taken in 1790. The early censuses were taken by sometimes minimally trained personnel called ‘enumerators’, who went from house to house to fill out their census forms. Such records are generally available from the first census through the fifteenth, taken in 1930. If you are interested only in censuses for your locality, they may usually be found at the public library of the nearest major city. Many have hard copies that may be viewed at the library, as well as computerized files that may be accessed by patrons. In utilizing local censuses, often the information is catalogued by political subdivision: township, ward, district, etc. Knowledge of the place of residence of your ancestor is necessary in using this type of record. Fortunately, many censuses now exist in databases searchable by surname, so that detailed information about residency need not be prerequisite. Such databases are often available for local areas. If a region outside your locality must be researched, many public libraries may acquire specific records from other cities or states, for your temporary perusal. Mormon Family History Centers, as well as many public libraries, subscribe to paid genealogy sites such as Ancestry.com, and have computers that may be accessed by patrons to view and search censuses from all states. Serious researchers can personally subscribe to such services. These services permit searches by first and last name, birthplace, and so on. But not all years’ censuses have the same level of detail of information. In 1790, enumerators asked for the name of the head of the family and the number of persons in each household that fit the following categories: free white males over age sixteen, free white males under sixteen, free white females, all other free persons, and slaves. By 1870, the census included the name of everyone in a household, along with information such as age, country of origin, value of real estate, citizenship, occupation and other data. The 1930 census is even more extensive, giving age, personal descriptions of each resident, year of immigration and naturalization if applicable, year of marriage, native language of the resident and his/her parents, birthplace (usually the country or state, sometimes the town), and occupation. A caveat in using the census is the sometimes horrendous spelling. Many Americans, immigrants and native-born alike, were illiterate. The spelling of their names was left to the mercy of the enumerator, who may not have been of the same ethnicity as the residents. In addition to simple misspellings, enumerators often got the gender of an infant wrong, especially when faced with an unfamiliar name like Gaetano or Felice. Sometimes gender was intentionally obscured by the parents, in hopes of avoiding military service for their sons. In sum, however, the U.S. Census is a very valuable tool for genealogical research. If you don’t have luck on your first attempt, try different spellings of the names. Another technique: if you remember the name of a neighbor of your ancestor, search for the neighbor. You may find your (misspelled) grandfather’s name at a nearby address! |

|

.

|

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry© Angelo Coniglio ~ October 2008 ~ Forever Young© WHEN A SEARCH WORKS . . . BUT DOESN’’t! Continuing our discussion of passenger manifests on ellisisland.org, a frustrating experience that often occurs is as follows: you find, on ellisisland.org, a name that fits your ancestor’s full name, town of birth, birth year, and place of origin. You expectantly click on the “Ship Manifest” and “Enlarge Manifest” links, and you see something strange: your ancestor was German, but all the names on the manifest enlargement are Irish, or your ancestor was Sicilian, but all the names on the enlargement are German! Further, the ship name at the top of the enlarged manifest is not the ship name shown on the text version! And your ancestor’s name appears nowhere on the enlarged manifest. What to do? The situation described above happens when there is an uncorrected “bug” in the Ellis Island data base. They simply have the wrong original manifest linked to your ancestor’s name. Fortunately, a researcher of Jewish genealogy, Dr. Stephen Morse, has provided on-line ways of finding the original manifest. He has a site which allows you to search the manifest of any Ellis Island-arriving ship for which the ship’s name and arrival date are known. Before you use Morse’s site, on the ellisisland.org “Original Ship Manifest” display, click on the “View Text Version Manifest” link, and from the resulting display, make a note of the ship name, arrival date, and the name of the first person (top line) in the list of passengers in which your ancestor’s name appears. Remember that you may also be able to get your ancestor’s name, ship of travel and departure date from his/her “Declaration of Intent” of naturalization, described in previous columns. Then go to http://www.jewishgen.org/databases/eidb/mm.htm and proceed as follows:

a) Click on

Ship-Lists, near the top of the

page.

d)

Click the name of the ship for the date which most closely matches the

information you have. When you click on the ship name for the voyage you want, a page will appear with the first page of the manifest for that ship and voyage. This is only the first page. Many manifests usually had 30 passengers per group, with one, two, or more pages for each group of passengers, and a total of thousands of passengers. At the bottom of the page are “buttons” which you can click to advance (or retreat) the image of the “roll” of microfilm by one, or the “frame” (page) you are seeing by one, two, three, or four frames. If you know the name of the first person in the list (from the ellisisland.org Text Version), you can click through the pages relatively quickly, until you see that name, and then scroll down that page until you see the name and other details about your ancestor. Be sure to check adjacent frames, to be sure you have all the information. If you don’t know the name of the first person on the list, I’m afraid you’ll have to look at and scroll down every page, until you find your relative. (No one said this would be easy!) Not all pages have actual passenger data and may be quickly skipped. My page at www.conigliofamily.com/ConiglioGenealogyTips.htm gives a more detailed explanation of this process with examples. Once you find the record you're looking for, make a note of the line on which the name appears in the list, and the Series, Roll, and Frame number, so you can find it again quickly. As I have said, the passenger record may have names of spouses or children that confirm it as your ancestor’s, based on prior knowledge. It may even have the name of parents or relatives left in the old country, or you may find a whole family group on several adjacent lines. Next time, I’ll discuss how to use this information to find Mormon microfilms of a person’s birth, baptism, marriage or death records, and how to obtain and use those films to trace interesting details of your ancestor’s history, and find even more ancestors! |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry© Angelo Coniglio ~ December 2011 ~ Forever Young© I’ll pause in my presentation of on-line methods for researching genealogy, to reply to questions from readers. I’ll pick up that topic again in coming issues, with Scotland and Ireland. Q: I’m sure my grandmother was Sicilian. She spoke that language, celebrated St. Joseph’s day and all the other holidays in Sicilian style, cooked Sicilian food, and so on, but she said she was born in Tunisia. How can that be, and how can I do research on her ancestry? ~ R.F.L., Kenmore, New York A: Around 1860, in the time of the unification of Sicily with the Italian peninsular states, there was extreme poverty in the Mezzogiorno (southern Italy and Sicily). After the formation of the unified Kingdom of Italy, much of the already meager wealth of the south was appropriated by northern officials and opportunists, and the peasants and laborers of the Mezzogiorno bore the brunt of the economic hardship. This social upheaval led to the ‘great migration’ out of the south, primarily to the United States, but also to Western Europe and even Africa, only 100 miles away across the Straits of Sicily. At the start of this period, Tunisia was under control of the Ottoman Turks, but in 1881, it became a French protectorate, until its independence in 1956. In the late 1800s and the early 1900s, Tunis and other coastal cities of Tunisia received the immigration of tens of thousands of Italian peasants, mainly from Sicily and Sardinia. As a consequence, by the first years of the 20th century there were more than 100,000 Italian residents in Tunisia, concentrated in the large cities of Tunis, Biserta, La Goulette and Sfax, and even in smaller cities. These immigrants established their own churches and neighborhoods, and while picking up the Arabic and French tongues, many retained their Sicilian and Italian language and social customs. Many made frequent trips back to their towns of origin, often convincing others to emigrate to Tunisia. Some who were dissatified with conditions in Tunisia eventually emigrated to the United States. So it’s not unreasonable to think of your grandmother as Tunisian and Sicilian. Passenger manifests at Ellis Island and other U.S. ports, available on the free site www.ellisisland.org and the subscription site www.Ancestry.com often show travelers’ last place of residence. Familiarize yourself with the names of Tunisian cities, as these manifests may indicate Tunis, Biserta, or the other large cities noted above, or smaller ones such as Zaghouan, Bouficha, Kelibia, or Ferryville. If your grandmother came here through a U.S. port, her manifest may give the name of the town she came from, and even name the closest relative she left behind. Certain Tunisian baptism, marriage and death records have been indexed on-line at http://www.geneanum.com/. You’ll have to read French, or get a French-speaker to help you, but that page gives links to helpful genealogical sites for Malta, Sicily, and Tunisia (Tunisie in French). Clicking on the Tunisie link leads to a page with the link ‘Bases de données’ (databases) and clicking there leads to choices for baptisms, marriages, and burials. Information on parents, spouses, etc. is shown in limited text form, but copies of original documents may be ordered through the site. Caution ~ given names are in French: Salvatore is Sauveur, Antonio is Antoine, Pietro is Pierre, and so on. Q: My grandfather was in the US Navy during World War II. I would like to find information about his Navy experience and the ships on which he served. ~ M.C., Norman, Oklahoma A: www.Ancestry.com has many historical military records, including US World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938 – 1949. These can be searched at http://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1143 for free at many public libraries or at a Mormon Family History Center. The database can be searched by the sailor’s name, date of service and location. The search results show images of original ‘ship musters’. Many such records have information on enlistment, assignment, rank or rating, etc. Once you find the names of the ships on which your grandfather served, search free sites like www.wikipedia.com to get more information about the ships, including photos. To see an example of my brother Guy’s pre-WWII musters, see http://www.conigliofamily.com/GuyPage2.htm. |

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry© Angelo Coniglio ~ July 2008 ~ Forever Young©

My list of three important elements necessary

to research an ancestor who immigrated to America are: One way is to visit the Erie County Clerk’s vital statistics storage area in the basement of the old County Hall on Franklin Street in downtown Buffalo (if you’re not in Erie County or your ancestor lived in another county, find that county’s corresponding office). Ask a worker there to help you with the naturalization records. There is a card file, alphabetically sorted, with indices of naturalization records from the early 1800s through the early 1900s. There are also several customer-usable computer monitors on which names can be searched. From the index, the staff can help you find the actual naturalization record, usual a “Declaration of Intent” that gives the person’s birthplace and date, and the date and port of emigration to the United States. Another source (not as detailed) is the person’s US Census Record for a given year. They are taken every ten years (1890, 1900, etc., and are available through 1930). Census records usually give a person’s approximate birth year, immigration year, age at marriage and birth country (not town). Some public libraries have US Censuses or Census Indices, from which actual Census records maybe ordered. The main branch of the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library has every Federal and State census on microfilm that exists for Erie County between the years 1790 and 1930. They also have some census records for other New York counties, and a few for the entire United States. If you have a Buffalo Erie County Public Library card, you can access all US Census records from your home computer. Contact any Library branch for details. The paid site www.Ancestry.com gives actual US Census images. Some years are available free from Ancestry.com on-line, at Mormon Family History Centers. The latter also have New York State Censuses, which were taken at the midpoints of the US Censuses (1915, 1925, etc.) Information from a census is often not precise, and you may have to search immigration passenger records for more information on the individual. This may be tedious, but if found, the record also gives a piquant bit of history about your ancestor. While the best-known site for ship passenger records is www.ellisisland.org, Ellis Island was open as an immigration site only from 1892 through 1924. From 1855 through 1890, New York immigrants landed at Castle Garden, and on-line records for these passengers are available at www.castlegarden.org. Other debarcation ports were Boston, Philadelphia, and New Orleans, whose records may be found at Ancestry.com. Old records may be rife with errors, some made by officials at the time of immigration, others made by Ellis Island, Ancestry, or Castle Garden computer staff in their data base entries. Your grandfather may have told his family that he was born in 1892, but a) he may have forgotten, or b) someone may have misread or miscopied the date. Don’t discard a lead just because the information is not exactly as you have been previously told. This also goes for names. As I’ve suggested before, be sure you know the person’s first name as it was used in his birthplace. As for last names, the on-line sites for census and passenger searches allow searches by last name, but the spelling of the name in the on-line record may not be the name you knew the person by. For one of many possible examples, say a person’s surname was Sorgi, and you have no luck searching on that name. Try Sorge, Sorci or Sorce, which all sound alike. You may also have to search for names that look alike. In the example, in script, the person who entered the name in the data base may have mistaken the “S” for an “L”, so you may have to search on Lorgi, Lorge, Lorci, or Lorce! Another trick: if the person was a woman and her maiden name was Sorgi, search for any young children she may have had, using their father’s surname. Since children often immigrated with their mothers, if you find the child, you may find the mother! Have patience. If you’re persistent (and lucky), you may find a passenger record that gives the person’s date of arrival, their town of origin, their parent’s (or other old-country relative’s) name, and the name, relationship and address of the person to whom they were going. Then you’re ready to look for their original birth record! |

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry© Angelo Coniglio ~ November 2009 ~ Forever Young© I have previously presented ways to find immigrants’ passenger manifests on ellisisland.org and by using Dr. Stephen Morse’s website at http://stevemorse.org/ellis/boat.html. Manifest images can also be found on pay sites like Ancestry.com. Once a manifest is found, a variety of information may be seen on it, depending on the years of immigration, the port of departure, etc. In addition to the name of the ship, the port and date of departure, and the port and date of arrival, early manifests (1880’s) may give simply the person’s name, gender and age. Some manifests show such information not only for passengers, but for crew members. Other lists may show names of passengers who have been “detained” for a variety of reasons. Later manifests give more information. Starting in 1907, the following data columns, and more, are listed: Family Name; Given Name; Age (Yrs. and Mos.); Sex; Married or Single; Calling or Occupation; Nationality; Race or People; Country and Town of last permanent residence; “Name and complete address of closest relative or friend in country whence alien came”; Final Destination (State, City or Town); and “Whether going to join a relative or friend, and if so, what relative or friend, and his name and complete address.” Remember that female immigrants from many European countries used their birth names, first and last, whether they were single or not. For example, my mother’s manifest gave her name as Rosa Alessi, and her son’s (my brother’s) name as Gaetano Coniglio. Don’t be thrown off a mother’s surname and the surname of her children, on the same manifest, are different. If the columns noted above are completely filled in, much can be learned. If you know the ancestor’s occupation in America, finding the same occupation listed in the manifest strengthens the case that this is the same person. Under “Name and complete address of closest relative or friend in country whence alien came”, the “address” that is given may be simply the town name, but usually under this heading the relationship of the person left behind is given. Much may be gleaned from this. For example, if it said “father” you would therefore know, if you didn’t already, the name of the passenger’s father. If the immigrant was from Sicily, Italy, Greece, Ireland or other countries with similar naming conventions, a man’s father’s name would be given to his first son, so if you know the immigrant’s oldest son’s name and it matches the name given on the manifest as his father’s, you have a strong correlation. Similarly, if the immigrant is a woman from any of the above countries, her second son’s name would probably be the same as her father’s. The “closest relative” named may be the immigrant’s mother: if her surname is different than the immigrant’s, that’s her maiden name, another piece of information that might extend or corroborate existing knowledge. The names of your ancestor’s eldest and second-eldest daughter’s could also be reflected in the n name of the mother. Or the name of the “closest relative” left behind may be that of a brother or sister, an in-law, or a spouse; in any case, it provides additional information about the passenger. Clearly, the column headed “Whether going to join a relative or friend . . .” can also provide very valuable information. Obviously, if the person was going to a spouse, and you already know the spouse’s name, a match is pretty strong evidence that immigrant is the person you’re looking for. Additionally, if a destination address is given, that may also match information from a Census, or give you a clue helpful in researching a particular locality for more information about the person. It also may add a “missing link” as to where an ancestor may have lived prior to any known places. In addition to the columns detailed above, manifests after 1907 also give the immigrant’s place of birth (usually, but not always the same as the “last residence”); whether literate; the amount of cash carried; whether ever in the US previously and when; condition of health; color of eyes, hair and complexion; height; and identifying marks. There are even such notations as “Whether a Polygamist” and “Whether an Anarchist”! I’m sure all anarchists declared themselves In future columns, I’ll discuss how to use Census and passenger manifest information to find Mormon microfilms of a person’s birth, baptism, marriage or death records, and how to obtain and use those films to trace interesting details of your ancestor’s history, and find even more ancestors! |

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry©

Angelo Coniglio ~ August 2009 ~ Forever Young© Primary records ‘Primary records’ are those recorded at the time of a genealogic event. A person’s birth record, noted in the permanent register of his town when his father reported the particulars of birth, is a primary record. The birth date on the person’s tombstone is a ‘secondary record’: the date was told to someone, then someone inscribed it on the stone. There is no absolute proof on the stone that the date is correct. One source of primary records is the Mormon Church, which has made microlfilm copies of original records from hundreds of towns and parishes. These are photocopies of original records, and as such carry the same weight. Previously, I have had more luck finding facts in the Mormon microfilms than I’ve had by trying to contact Sicilian towns or churches by mail, e-mail, or even by personally visiting the town. But after my most recent trip to Sicily, I learned a lesson about primary records. The names that follow have been changed, but the story is absolutely true. I had long searched for the ancestry of a relative, Maria Galbo, born in Belpaese in 1883. The image of her birth record on the Mormon microfilms stated that her father was Ciro Galbo, born in 1855, and that her mother was Lena Marino, born in 1861. I also found the filmed 1855 birth record for a Ciro Galbo. His mother’s first name was Maria, which supported the idea that he could be the father of Maria Galbo. But I could find no record for Lena Marino: in fact, I could find no record of anyone with the surname Marino in any of the records of the town for 100 years, except for one person born many years before 1861. Further delving into the films, I found an 1879 marriage record for Ciro Galbo, but it said that he had married Lena Messina (not Marino). All my searches of films for any birth, baptism, marriage or death record for Lena Marino were fruitless. Neither could I find Ciro Galbo’s death record, which may have confirmed the name of his widow. Although I found ancestry for Ciro Galbo and Lena Messina, I didn’t add the information to my genealogy records, afraid I was ‘barking up the wrong family tree’. Was my ancestor Lena Marino or Lena Messina? When I re-visited Sicily this spring, I resolved to unravel the mystery. I went directly to the Belpaese Muncipio, the Town Hall, and asked to see the death record of Ciro Galbo, hoping that it would give the name of his wife. Unfortunately, no such record could be found. The records clerk suggested that we look at Ciro Galbo’s birth record, and I agreed without much enthusiasm, since I had already seen the filmed copy. But when the original record was retrieved, at the top I saw a ‘margin note’ that had not been present on the Mormon copy. It was written many years after the actual birth, and said: “He (Ciro Galbo) married Lena Messina in 1879. He now lives in Nantrabanna. His wife is here (in Belpaese) and she wants to be called Marino.” Eureka! Lena Messina and Lena Marino were one and the same, so one mystery was solved (leaving another one, discussed a little later). When I saw the revealing margin note, I asked whether I could have a photocopy of the birth record. The records clerk shook her head and said that for privacy reasons, it wasn’t allowed. I started to copy the information by hand, when the clerk’s assistant asked me if I had a camera. My face brightened, but again the clerk solemnly said “No!” Photographs were not allowed, either. They must have seen my crestfallen look, because the clerk suddenly lowered the window blind. Then her assistant locked the door, winked and said “We see nothing!” I got my photo of the elusive record. The new mystery I alluded to is the fact that the Mormon record I found on microfilm (made only a few years ago) doesn’t show the margin note about Lena Messina/Marino. How could that be? Aren’t the microfilms copies of original primary records? The answer is that back in 1855, the town clerk of Belpaese painstakingly, by hand, filled out two birth records, both considered primary records. One copy went to the capital city of the province in which Belpaese is located. That copy was ultimately photocopied by the Mormon Church, and found by me in my reasearch in the U.S. The other copy was bound in the permanent register of the town of Belpaese. Years after the 1855 birth, a clerk in the town added the margin note, and well over a hundred years after that, I found the note, during my personal voyage of discovery. The moral is: there are primary records, and sometimes there are other primary records. The Mormons’ on-line lists of available microfilms indicate where those photocopies were made. If they were made from records in the provincial capital, there is a possiblity that duplicate records exist in the town of origin. It is also possible that data for specific events or for whole years, listed in the provincial records as missing or damaged, are still on file in the town of origin. Conversely, if films were made of a town’s records, and the town’s records were subsequently damaged or lost, more complete copies may exist in the provincial capital. The only way to tell for sure is to view the records ln the ‘old country’, or have someone do it for you. |

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry©

Angelo Coniglio ~ December 2008 ~ Forever Young© What can be found in Original RECORDS? Amateur genealogy researchers are often most interested in finding birth records of their relatives or ancestors who immigrated to the United States. Before we discuss birth records in detail, I’ll summarize the various types of records that might be available for a particular European town. Not all have all the types of records discussed. Some may have films with gaps in the record, and some, unfortunately, may have only one of the types mentioned, or more sadly, none at all. If there is no film available, that does not necessarily mean there are no records, only that for whatever reasons, the records were not made available for microfilming. Church records may include records of baptisms, births (separate, or as indicated in the baptism record), confirmations, marriage banns, marriages, and deaths. (All Catholic church records were usually in Latin, regardless of the country involved. Other Christian churches may have used Latin or the national tongue.) Civil records may include records of births, marriage banns, marriages, and death Censuses may include information on property ownership or rental, and some family relationships. The Mormon Church’s films of civil birth records, when available, generally cover the period 1820 through 1910. In much of Europe, civil records were standardized by order of Napoleon. Even though the earlier records are completely handwritten, the scribes followed essentially the same format for each record. After about 1870 (depending on the nation involved), pre-printed forms were used, and the clerks simply filled in the names, dates, and pertinent facts. The good news about the earlier records is that they sometimes included more information than the more recent records: the bad news is that they are fully handwritten, and some clerks had poorer handwriting than others. Even on the later records, the handwritten portions may be difficult to interpret. Many genealogy books have examples of handwriting from that era, which can be used as a guide. The civil records, of course, are in the language used in the nation where the record was made. This brings us to a question. If the records are in French, or Italian or German, and you don’t speak or read the language, how can you understand the records? First, I advise you to try to learn at least the basics of your ancestors’ native tongue. You don't have to be an accomplished linguist. At least learn enough to recognize what your relatives' names were in their own tongues. Talk to your parents or older relatives, buy a German-English dictionary, etc. to get a rudimentary knowledge of the language’s names and words. You can search on-line for books with titles like “Finding Your (French, German, etc.) Ancestors”. Such books not only give advice on how to do research, but often contain a translated glossary of numbers, names, occupations, and common phrases. Similar books are available for several nationalities. If you really have a hard time with the language, FHC volunteers or other researchers are often willing to help in translations. The records must be viewed at the FHC, on a microfilm reader. What we call “birth certificates” were not used. The births in each year were recorded sequentially in a large ledger. Civil birth records generally include, for each year, an index of all the year’s births. These are usually, not always, directly after the records for a given year. Start your search with the index. In the best case, indexed names are alphabetized, and each has a number before or after it showing the number of the page or record for the person. The actual record can contain valuable bits of information, as follows (underlined items are often found in older fully handwritten records, but not in more recent ones): record or page number; child’s name; record date and time (not necessarily the same as the birth date); birth date; father’s name; paternal grandfather’s name; the father’s age, occupation, and address; mother’s name (including maiden name); the maternal grandfather’s name; and the mother’s age and occupation. This data is often followed by names, ages, and occupations of witnesses (not to the birth, but to the recording of the birth), and by a statement saying that the act (record) was read to all present and signed by those who knew how to write. This can be an unexpected bonus: If your ancestor’s father knew how to write, you’ll see an image of his signature! Knowing the father’s (and sometimes the mother’s) age is invaluable: subtract it from the year of the record, and you’ll know (approximately) when the father was born. You can now obtain the film for that year and the years around it, and search for the previous ancestor. |

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry© Angelo Coniglio ~ November 2008 ~ Forever Young© CIVIL BIRTH RECORDS If you have been lucky in finding the actual name, date (with year) and place (town) of birth of an ancestor or relative from “the old country”, you are now ready to try to find an actual birth, baptism, marriage or death record. These records (or photocopies thereof) are called “Primary” records. They are on-site records of the information as originally recorded.

One way to see these records would be to

physically visit the town, go to the proper church, cemetery, or civil

office, and ask for the records. This could be expensive, not to mention

difficult, if you don’t speak the proper foreign language (though I

encourage anyone who knows the place of their original roots to visit if

they can, not just for records, but to experience the surroundings where

their ancestors lived). An alternative would be to pay a professional

genealogist to search for the records. This, too, can be expensive, but

dozens of such researchers can be found by on-line searches for

“genealogy”. Another approach is to write to the church or civil

authorities, asking for specific information. To do so you must go on-line

and learn the addresses of the offices you wish to contact. Again, you must

know the foreign language in order to write the letters. Many books like

“Finding your _______ Ancestors”, which I have mentioned before, give

translated form letters which may be used for this approach. I have never

had any luck with this approach, after several attempts.

After you’ve done this, go back to the

previous page, and under the “Library” dropdown menu, select “Library

Catalog”, and then “Place Search”. The resulting page allows you to search

for films from the town you’ve identified as your ancestor’s origin.

Following the links will eventually show whether there are Church, Civil, or

Census records for your town of interest. There may be many, or only a

few, or unfortunately, sometimes none. Most European nations began using

standard civil records under the orders of Napoleon in the early 1800’s,

though many churches have records from the 1600’s. Church records are

generally in Latin, regardless of the country, while civil records and

censuses are in the language of the nation of origin. There are numerous published books (addressing numerous nationalities) that have titles like “Discovering Your German [or Polish, or Italian] Ancestors”. I do not endorse any particular book, but a search at your public library or on-line should reveal a few. Many of these books have photo-reproductions of specific original birth, marriage, etc, records. Because part of the problem in reading them is not only the language, but the archaic handwriting, many books show the original record, then a transcribed record (still in the original language, but with readable text), and then a translated record, which translates both the official form and its entries into English. In most cases, each country or region had a fixed format for these records. Once you see one translated, all you have to do is figure out the names, dates and places in your document, and fill them in to the appropriate places in the book’s translated document. Such books often include some form of translation dictionary for common genealogical phrases, numbers, occupations, etc. The LDS, for privacy reasons, has no records available after 1910. If there are records for your town, a list of all available microfilms can be printed. For large cities or towns, there may be many films, with only one or two years per film. Smaller towns may have ten years or more of records on a film. Generally, films have only one type of record (e.g. births), but may have more than one type of record. If you have trouble identifying the films using your home computer, volunteer librarians at your nearby LDS FHC can help you find them. Once you find the film that covers the birth year of your ancestor, you can go to the LDS FHC and order the film. $5.50 will allow you to get the film in about a week, and use it at the FHC for one month. After a month, it can be renewed for another $5.50 and used at the library for another two months, and finally, for another $5.50, in can be placed on “Extended Loan” and used indefinitely. Though you may at first be interested in only one person on the film, you may find that there may siblings or other relatives on the film and keep it available for future review. Films already at the FHC which have been rented by others are available for your use, as your film will be to others. |

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry©

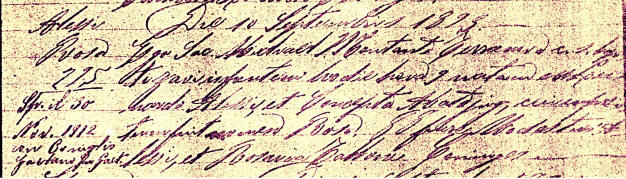

Angelo Coniglio ~ January 2009 ~ Forever Young© A UNIVERSAL LANGUAGE ~ CHURCH BIRTH/BAPTISM RECORDS Last month, we discussed civil birth records from European towns. I neglected to note that in addition to the birth information found on the record, often, there were "margin notes." These were notes that were added years later by the town clerk, and might give, for the individual whose birth was recorded, information such as the person's date and place of death, or his/her marriage date and place, with the name of the spouse and possibly the spouse's father. Other information in a margin note may correct previous errors, such as the misspelling of a child's name, or a mistake in first recording the baby's sex. Often, church records may reinforce information found in civil records, or fill in gaps when civil records are missing. These gaps occur when records have been destroyed by fire or civil disorder, or when towns have refused to allow Latter Day Saints representatives to microfilm their civil records. Another advantage of church records, in some cases, is that they may be available for periods much earlier than the 1820s, and often back to the late 1600s. The disadvantage is that they are almost always handwritten, and indexes are usually not annual, but may include records of ten or more years. Also, indexes may give only the page of a record, rather than a record number. Individual church records are rarely as informative as civil records, and actual birth records were often not kept. Rather, a child's baptism was recorded, and the day of birth might be noted in the baptism record. These were rather brief, and often gave only the date of the record, date of baptism and birth, the name of the baptizing priest, parent's names, and godparent's names. No ages of any of the adults were given, but in some cases the grandparents' (or at least the grandfathers') names were given, and sometimes the relationship of the godparents to each other was given. This could be valuable, since godparents were often relatives of the child. Church records also may contain margin notes. Latin was nearly a universal Catholic church language used in many countries, while other Christian churches may have used the national language, or Latin. The example given here could be from any country. I also give a translation of the record, which happens to be of my mother's baptism:

The recorder of this baptism did not hyphenate words. When he reached the end of a line, he simply began on the next line with the rest of the word. Note that the record does not give the birth date, which was actually September 9, 1893. I knew from other research that Modesto Alessi was my mother's great-uncle, but before I found this record, I did not know that his wife's name was Rosaria Tabbone. The record includes a margin note added by a church scribe 19 years after my mother's birth, which (in Italian) says she was married on November 30, 1912 to my father Gaetano Coniglio, and that his father, also named Gaetano, was deceased by 1912. My father was a youngest son, and this is an example of naming a child, born late in the father's life, after the father. An interesting aspect of this record is that my mother always recorded her anniversary as given above, November 30, 1912, but both her civil marriage record and the margin note on her civil birth record say she was married on December1, 1912. That's because the church and civil authorities were in a period of conflict, and in order for a marriage to produce legitimate heirs, the couple had to be married in a civil ceremony. So, the day after they were wed in Church, they went to the town hall, and were married again! The records must be viewed at the FHC, on a microfilm reader. What we call “birth certificates” were not used. The births in each year were recorded sequentially in a large ledger. Civil birth records generally include, for each year, an index of all the year’s births. These are usually, not always, directly after the records for a given year. Start your search with the index. In the best case, indexed names are alphabetized, and each has a number before or after it showing the number of the page or record for the person. The actual record can contain valuable bits of information, as follows (underlined items are often found in older fully handwritten records, but not in more recent ones): record or page number; child’s name; record date and time (not necessarily the same as the birth date); birth date; father’s name; paternal grandfather’s name; the father’s age, occupation, and address; mother’s name (including maiden name); the maternal grandfather’s name; and the mother’s age and occupation. This data is often followed by names, ages, and occupations of witnesses (not to the birth, but to the recording of the birth), and by a statement saying that the act (record) was read to all present and signed by those who knew how to write. This can be an unexpected bonus: If your ancestor’s father knew how to write, you’ll see an image of his signature! Knowing the father’s (and sometime the mother’s) age is invaluable: subtract it from the year of the record, and you’ll know (approximately) when the father was born. You can now obtain the film for that year and the years around it, and search for the previous ancestor. |

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry©

Angelo Coniglio ~ March 2009 ~ Forever Young© Wedded BLISS Among the records microfilmed by the Mormon Church are local European church and civil records of marriages. Like other records, these may have been in the language of the country of residence, which was usually the case with civil records; or in Latin, especially if they were recorded at a Catholic church. Marriage records took many forms, but like birth records, were not commonly produced as “certificates”, but rather recorded in the permanent record ledger of the town or church. In addition to an actual record of marriage, various ancillary records may exist, depending on the country and town. These may include: wedding banns, notices that were required to be posted in public to make the community aware of the impending union; attachments of birth records of bride and groom, their parents, and even their grandparents; and finally records of the actual marriage. “Banns” in Spanish is “amonestaciones”; in Italian it’s “pubblicazione”; in French it’s “bans”; and in German, it’s “Aufgebot”. In Spanish, “attachment” is “accesorios”; in Italian it’s “allegati”; in French, it’s “fichiers”; and in German, “Ablage”. And “marriage” is “matrimonio” in both Spanish and Italian; “mariage” in French; and “Verbindung” in German. In the Napoleonic format, along with the date, time and place of the wedding, civil marriage records gave (in the best of cases) the name and age of the groom, his birthplace and domicile, his father’s name, age, and occupation, and his mother’s name. The same information was given for the bride. In addition, it was noted whether the bride and groom were “celibate”, or previously unmarried. If either had a previous spouse, the proposed bride or groom was identified as a “widow” or “widower”, and the name of the previous spouse was given. The record may also have the names of two to four witnesses (to the record, not necessarily to the marriage!) As with other records, the date of marriage may have been different from the date of the record. When a parent’s name was given in a birth, death, or marriage record, often the father of the parent was also identified. For example, in Sicilian records, if Giuseppe Amico was the spouse, his father’s name might be given as “Salvatore di Giuseppe” or “Salvatore fu Giuseppe”. The former means “Salvatore, son of (the living) Giuseppe”, and the latter means “Salvatore, son of the late Giuseppe”. Thus, some information about the death of the groom’s grandfather is presented. The father and grandfather’s surname is not repeated, as it is the same as the groom’s. Naming the father’s father would occur if there was more than one “Giuseppe Amico” of marrying age in the town, to distinguish the new bridegroom from others. Similarly, the bride’s father and grandfather might be named. In this case, the name of the groom and his grandfather was the same. In Sicily, that would likely mean that the spouse was an eldest son. The marriage banns, of course, are not actual marriage records, but notices of intent to marry. Nevertheless, they identify the potential newlyweds and their parents. Since they were issued before the actual marriage the date of the wedding is not given, but the information is essentially the same as that given in the eventual marriage record. Even if the marriage record cannot be found, where later evidence (e.g. the spouses’ death records or their children’s birth records) confirms that they were married, the banns can provide valuable information. Banns may list the documents presented to prove identity, etc. Civil records often included such a list of attachments: copies of the groom’s and the bride’s birth records; the birth records of their parents; the death records of their fathers or grandfathers; and the death records of any previous spouses of the newlyweds. In some (fortuitous) cases, the names of the actual persons are given in this list, but most often a generic description is used, like “Death record of the father of the bride.” However, if the researcher is truly lucky, the marriage records may include actual attachments, such as extracts or handwritten copies of the birth, death, or other records listed in the marriage record. These can be a real find, since, for example, a grandfather’s death record may also give the name of his father, etc. Finally, the genealogist’s “treasure trove” may be found: churches often required that bride and groom must have a certain degree of familial separation. That is, first cousins could not marry one another; second cousins could marry only with church approval, and so on. In some villages, in order to confirm these relationships or their absence, an actual ancestry chart or list was included, showing the names of antecedents three or four generations back! |

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry©

Angelo Coniglio ~ February 2009 ~ Forever Young© The REAPER’s Tale In a previous column I presented a baptismal document in Latin, and said that church records were usually in Latin. I should have said that Catholic church records were usually in Latin. Other Christian churches may have used Latin or the language of the country of record. We have discussed birth and baptismal records, and shown how they may be useful in extending knowledge of ancestors to earlier generations. Surprisingly, both civil and church death records can do the same. Death records come in a variety of forms and languages, depending on the date, and on the location of the record. Early Catholic church records are available in Latin and later civil records use the national tongue. As is the situation with births and baptisms, these records are not what we today would call “Death Certificates”. They are records kept in the permanent ledgers of the church or town having jurisdiction. The fullest records, such as they are, are in these archives. A request to the church or town may result in an “extract” which gives less information than the original record. As for all such documents, care must be taken to distinguish between the date of the record and the actual date of the event (death) being recorded. Besides the record date, and the deceased’s name, date of death and age at death, church ledgers give the parent’s names if the individual was single at death. The parents’ ages are generally not given. The surname of the father is either given or assumed to be the same as that of the deceased. Often the surname of the mother is not given. If the deceased was married, the parents’ names might be given, but sometimes the only name given might be that of the decedent’s spouse. Remember that in many countries, there was no practice of “maiden names” – a woman could be known by her birth name for her whole life. A typical church death record (translated) might read: “Speck Marta: 22 October 1795, age 37 years died yesterday. Daughter of Johan and the late Anna. Widow of Ludvig Schulz. Buried in the public cemetery” This might not sound like much, but from these few lines, it can be determined that Marta was born in about 1758 and died October 21 1795; that her father Johan Speck was still living in 1795; and that her mother Anna (last name unknown) and Marta’s husband Ludvig Schulz had died before 1795. If other records had shown a Marta Speck or Marta Schulz who had children named Johan, Anna, or Ludvig (continuing family traditions), that might indicate that the two Martas are one and the same. Because of naming conventions peculiar to the country you are researching, you may have to look for death records (in our example) for Marta Speck or for Marta Schulz. Later civil death documents from countries using Napoleonic-style record-keeping gave somewhat more information. In addition to the information noted above, civil records might give the decedent’s town of birth, occupation and last address, as well as the occupation of his/her parents and/or spouse. If the deceased had been married more than once, often the names of other spouses were given. Civil records also may show names, occupations and addresses of witnesses reporting the death. These may have been relatives of the deceased. Causes of death were seldom given. As previously noted, birth and baptismal records sometimes were annotated in the margins with information on marriages or other events. Sometimes such notes also include the person’s date and place of death. The death information given in these notes allows the actual death record to be looked up in the appropriate archive. Finding specific death records is generally more difficult than birth or baptism records, which can be deduced from the records of descendants. Deaths are more random, and sometimes require the perusal of many years’ ledgers before they are found. Notations on other records may help. For instance in the example presented above, we know Ludvig Schulz died before 1795 and we can guess that his wife Marta was at least 15 when she married him. That would mean he was living in 1763. So he died between 1763 and 1795. That’s “only” about 32 years of records that we have to search! If there are records of Ludwig’s having children born after 1763, that would reduce the length of the time “window” to be investigated. |

|

.. |

|

Finding Our Immigrant Ancestry ~ Angelo Coniglio MULTIPLE RECORDS Often, I have had more luck

finding facts in the Mormon microfilms than I’ve had by trying to

contact Sicilian towns or churches by mail, e-mail, or even by

personally visiting the town. But after a trip to Sicily, I learned

a lesson about primary records. The names below have been changed,

but the story is factual. Angelo F. Coniglio is a genealogy researcher and author of the fictional historical novella The Lady of the Wheel, set in 1860s Sicily. The book may be ordered from Amazon.com, at http://www.bit.ly/racalmuto. Genealogy questions? E-mail Coniglio at genealogytips@aol.com |

|

The Search for our Ancestry© Angelo Coniglio ~ April 2009 ~ Forever Young© Records, records, records I have discussed finding and interpreting various records from primary old-country sources such as birth, baptism, marriage and death records. Many who are interested in tracing ancestry or finding living relatives may need to research local, county, state, or federal records. In this space, I’ve previously briefly spoken about those. I have concentrated on how records in this country may help establish the three ‘key data elements’: 1) Name; 2) Birth date; and 3) Town of origin. If the person was an immigrant, another important datum is 4) Date of immigration. I’d like to review how these data may be found, and how they may be used to trace information on individuals who were born not only abroad, but in this country. Of course, the simplest way to get the information is family knowledge: your mother tells you her grandfather’s name, his birth date, where he was born, and if an immigrant, when he came to America. If she does so, there’s no problem, right? Well, did she give you his Anglicized name or the name on his birth records, which would give the name in its German, French, or Italian form? Was his birth date from memory or some document in her possession? Is she specific about his birthplace or did she just know the county or province? And if she also gave you the same information on your grandmother, did it include grammy’s original given and birth surname, or her married name? If the family information is all ‘good and true’, you can proceed to try to find the other types of records we have spoken of. But if not, the information has to be ‘cleaned up’. Name: If you know the person’s Anglicized name, there are numerous sources to determine the name in its original language. For Italian names, I have a list at http://www.conigliofamily.com/ItalianNames.htm. For other languages, try the internet. For example, http://www.behindthename.com/translate.php lets you enter a name in English, then find the name in many other languages, and even in nickname or short form, or in masculine or feminine form, in those languages. But be careful. Looking up the Italian translation for “John” on the above site, I found they give 23 alternatives, including ‘Giovanni’, but they don’t tell you that the American ‘John’ is most likely derived from ‘Giovanni’. If you are checking a surname, the internet may be helpful as well, especially in presenting valid spellings of surnames whose spelling has changed over the years. The sites are too many to give here, but a Yahoo! search of “Surnames” will give many alternatives. Birth date: (I’m assuming you’re looking for the person’s birth record and don’t have it in hand.) Tombstones are one source. Later records such as marriage certificates, etc. may help, as may naturalization records. These sources are secondary (someone told someone else what the date was), and may not be exactly correct. Don’t ignore a record that doesn’t agree with a long-held family opinion about a birthday. Death records may give the decedent’s birth date, These may be found at local archives, or on-line in Social Security Death Indices, but may require purchase of membership to a genealogy site such as Ancestry.com. Local archives or on-line sites may also have WWI or WWII draft registration information, or passport information, any of which may give birth dates. Town of origin: This is a critical item, and may be difficult to determine if family lore doesn’t provide it. For many years, one step in an immigrant’s naturalization was the filling out of a ‘Declaration of Intent’ or ‘Petition for Naturalization’ of the US Department of Labor’s Naturalization Service. This form can be a treasure lode, as some versions include all of the key data: name, birth date, town of origin, immigration date and even the name of the ship of passage. Local city, state or county archives may contain these records. Date of immigration: This is noted on the forms described above, but if those are not available, other sources may help. Primary among these are the US Census records. These are public records, available in various formats for every tenth year from 1790 through 1930. The earliest show little more than a person’s name and home town, while the later ones give names of all family members, street addresses, ages, country of birth (in rare cases town of birth), age at marriage, primary language, year of immigration, year of naturalization, and occupation. This information is secondary, not precise, and may be incorrect, but used with other records, it may help to ferret out important facts. |

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry© Angelo Coniglio ~ June 2008 ~ Forever Young© A Rose by any Other Name This month’s column is prompted by a recent piece in a local newspaper, describing this season’s “most popular names for babies”. It presents names like Eliott and Bradley (both “out”), and Declan or Griffin (both “in”). First names today have less to do with family or cultural traditions and more with the sound of the name combined with the surname, the “shock” appeal of a “different” name, or just the “cuteness” of the name. Little thought seems to be given to what the actual origin or meaning of the name may be (if it’s not just made up), nor the place of the name in the great sequence of family ancestors who preceded the child from time immemorial. This is not a criticism of parents’ naming any child whatever they like, which is, after all, their right. It is more a comment on how names in the past were assigned. Many nations and regions had specific naming custom and traditions, which can turn out to be a great help in finding ancestors and building a family tree. In Poland, it was common to name a child for the saint representing the date of birth; in Italy and Sicily, there was a fairly rigid practice of naming the first son after the father’s father, the first daughter after the father’s mother, the second son after the mother’s father, and the second daughter after the mother’s mother; Germany sometimes used a combination of these methods, giving the child a “spiritual” or saint’s name, then a true “first” name derived from an ancestor in the Sicilian style. The spiritual name might have been Johan, for example, and all male children would have this spiritual name, followed by their “first” name: Johan Anton Mueller, Johan Petr Mueller, Johan Georg Mueller, etc. In everyday life and in business and marital records, the child was not called by his spiritual name, but by his “first” name. Later records could be confused by record-keepers’ assuming the “spiritual” name (since it preceded the other names) was the first name, and dropping the true “first” name, thus listing several children of the same parents, each with different birth dates, but all shown as “Johan Mueller”. The Sicilian method can be confusing, since a man who had five sons could then have five grandsons, all with the same name as he! However it can also be useful. If a person is searching for his Sicilian grandfather’s records, but doesn’t know his name, I ask “What was your eldest brother’s name?” Whatever it was, the odds are that it was also the paternal grandfather’s name. In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, Italians and Sicilians did not name children after themselves, except in special cases: after a couple had had ten or twelve children, the youngest may have been named after his father; or, if a man died while his wife was pregnant, the baby was named after him. This was true even if the child was a girl: she would be given the feminine form of her father’s name: Michela for Michele, Gaetana for Gaetano, Angela for Angelo, etc. Only after immigrants came to America (possibly because their parents were not here to explain or enforce “the rules”) did it become common for a man to name his son “Junior” after himself. “Junior” did the same thing, and then had a proliferation of Joseph III’s, Joseph IV’s, etc. Another important aspect

of names in research is the difference in spelling of the name in different

documents. If you are searching old-country records, you must know

the spelling of the name in the original language. If you’re researching

American records, you must know the English version, its spelling, and

possibly the nickname that might have been used. Carmela Anzalone would

have been just that in Italian records, but her American census might have

shown Carmen, or Millie, Mildred, or even Nellie! There are numerous

websites which give American equivalents of foreign names, for example, use

the following, or “surf the net”: |

|

. |

|

The

Search for our Ancestry© Angelo Coniglio ~ August 2008 ~ Forever Young© A Little help from my friends An example of a "genealogical puzzle" might be like the following: A family bible passed down from a great-great-grandfather says in part: “traveled to Buffalo on the Erie Canal, 1828”. The family has lived in the western United States for three generations, and they would like to know if there is any official record of his immigration through Buffalo.

In its heyday, more people passed through the Canal District in Buffalo, on

their way west, than passed through Ellis Island. Unfortunately, because it

was internal travel, detailed records were not required, except for a period

from 1827 through 1829. If an ancestor came during that time, one could try

to find pertinent information at: The city of Buffalo had its beginnings as a small village on Buffalo Creek (today, in Buffalo, it’s called the Buffalo River), adjacent to a Seneca Indian village. When the famed Erie Canal was being planned, the Village of Buffalo fought for and won designation as the western terminus of the Canal. Its main competitor, the Village of Black Rock, is of course, now a neighborhood in the City of Buffalo. The Canal was the impetus for Buffalo’s transformation from a tiny village to one of the nation’s busiest and largest cities, and completion of the Canal in 1825 formed part of a boundary around a famous (or infamous) district to be known variously as “Canal Street”, “Five Points”, “Dante Place”, the “Hooks”, and other colorful names. By 1832, the Canal had made Buffalo so prosperous that it had expanded outward from the Canal District and incorporated as a bona fide City. It also enabled New York City to become a major eastern port that could easily ship passengers and products west. What does this have to do with genealogy? The builders of the Canal were mostly of Irish descent, and when the Canal was completed, many remained in Buffalo, forming the base of its large Irish community. Blacks came to Buffalo on the “Underground Railroad” which passed through the District, and many remained. Immigrants from across Europe may have landed on the east coast, but if America’s west was their destiny, a multitude passed through Buffalo. And finally, in the 1920s, the Canal District became “Dante Place” or “Little Italy”, where thousands of Italian, mostly Sicilian immigrants lived elbow to elbow in crowded tenements; buildings whose only saving grace was that they had replaced the one-time dives and brothels with honest, hard-working (though crowded) families that dreamed the American dream, and who finally lived it. To see a map of the Canal District during those days, and an overlay of the existing area (now essentially the Marine Drive Apartments), see http://www.conigliofamily.com/Buffalo.htm The title of this month’s column is “A Little Help From my Friends”. I have long envisioned, for Buffalo, an Erie Canal Museum that would not only hold artifacts, literature and mementos, but a Library which holds records on the people of the Canal District. A library which like Ellis Island would be accessible not only in person, but on-line, allowing family members across the nation to trace their ancestors who were in some way connected to the Canal. If you had family, of any nationality, who helped build, or labored on, or immigrated on the Erie Canal, or who once lived in the “Hooks”, I ask that you write or e-mail me with information about them: where they came from, where they were bound, where they lived, what they did, and in what years they were involved in any aspect of the Canal District. I’ll begin to form a data base from this information, and make it available to others (perhaps your own long-lost relatives or their friends) who hope to find a missing piece of information about their ancestors. Ideally, I’d like to collect information from families, libraries, and newspaper archives from around the country. If we’re successful, perhaps the powers that be will realize that an Ellis-Island type museum, with an “Erie Canal Wall of Honor” can be a civic and economic boon to Buffalo. This idea was inspired by the wonderful book by Mike Vogel, Edward Patton, and Paul Redding, “America’s Crossroads ~ Buffalo’s Canal Street/Dante Place”. If you would like to read more about the concept, see http://www.conigliofamily.com/BuffaloErieCanalFoundation.htm Of course, as usual, I welcome any questions you may have on other aspects of genealogy.. |

|