In April, 2004, Aunt Angie and I (Uncle Angelo Coniglio) visited Robertsdale, in Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania. We toured

the

Broad Top Area Coal Miners Museum and the Italian Cemetery, and

spoke with Research Librarian Carolyn Carroll and staff members Margaret Duvall and Dennis Fields;

with John Ciampa, a director of the Broad

Top Area Coal Miners Historical Society;

and with Bill Rourke and Jim

Territo, long-time residents of Robertsdale.

The material below was derived from our

conversations with them, from news articles posted at the museum, and from books written

by

Ron Morgan, a Robertsdale native and conservationist. All of them were very

helpful, and their fierce pride in Robertsdale's history is evident. I also

spoke on my return with Russell Asarese, born in Robertsdale in 1914, and a Buffalonian since

1926.

[Briefly, as stated on the Robertsdale page, Giuseppe

Coniglio came in 1912 and

was joined in 1913 by his wife Angela

Alessi Coniglio, accompanied

by his brother Gaetano

Vincenzo Coniglio. Gaetano's wife (and Angela's sister) Rosa Alessi Coniglio and their son Gaetano Vincenzo (Guy

Vincent) joined him there in

December 1914. For a time, Gaetano also lived and worked in Pittston, in eastern Pennsylvania.]

Unlike many inexperienced immigrants,

Giuseppe, Gaetano, and

their countrymen (paesane) from Serradifalco were seasoned miners. They

were hired by the Rockhill Iron and

Coal Company to mine bituminous

or "soft" coal from deep mines near Robertsdale. The miners were

virtually "owned" by the company, and about the only place they could

spend their wages was at the company

store. They were required to provide

their own tools (sometimes home-made to save money), and even to buy their own blasting

powder (from the company store). They were paid not by the ton, but by the

"yard", that is, the depth of the coal they excavated from the mine wall each

day.

The homes were built and owned by the company,

and much of the miner's pay went towards renting them. In the January 1920 Census,

Gaetano (listed

as "Guy") and Rosa (listed as "Rosy"), their last name

mis-spelled as "Comellia", were shown as renters of 100 Spring Street, Robertsdale. Listed as their children were Guy, age 6; Leonardo, age 4 years and 2 weeks; and Raimondo, age 3. Felice was born in December, after the census was taken.

The Coniglios' neighbors, at 96 Spring Street, were Calogero and Grace Asarese Butera,

also from Serradifalco. Grace was the granddaughter of another Grace Asarese, who

has one of the few marked graves in the Italian

Cemetery (photo below). The grave was

frequently visited by her grandson Russell Asarese (Grace Asarese Butera's brother) of

Buffalo. The other photo below shows an existing house on Spring Street, believed to

be the last home remaining from the 1920s.

There was no electricity, and the streets were dirt, covered in cinders. There was

no running water: the women and children carried water for cooking and laundry, from a

natural spring at the end of Spring Street. The town had a public school which Guy Jr. may

have attended, but the Catholic church was not built until 1922, next to the

Italian Cemetery. Before the church was built, a visiting

priest would hold masses, christenings, and marriages in available buildings. In

1918, the town's movie house, the Liberty

Theatre, was built on Main

street. The theatre burned down in 1936. In 1948 it was rebuilt and re-opened

as the Reality Theatre, and the building (photo below) is now the home of the Broad Top Area Coal Miners Museum.

The three boys born in Robertsdale were baptized

from the Immaculate Conception Church, in Dudley, Pensylvania, four

miles away; either in the church itself or by a travelling priest from that

church. See the pages of

Leonard,

Ray, and

Felice for their baptism records.

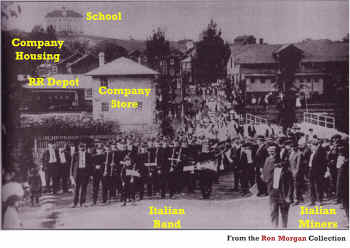

Robertsdale also had an

"Italian

Band" which was renowned in the area, and the focus of attention

at Italian gatherings, especially every Columbus day, which the miners wanted as a holiday

from work. [See photo below]

The men were strong union men and

good workers

who on a normal day did not see the light of day: they entered the mines before dawn and

returned after dark. This led to several strikes for better working conditions,

including one in 1916 and another in 1922. While the men were in the mines, the

wives fetched water, took care of the homes and children, and sometimes did laundry or

house-cleaning or took in boarders for extra income. And they prayed that their men

would come home safely. The immigrants came from a small, remote mountain town in

Sicily to a small, remote mountain town in Pennsylvania. In an already isolated

town, they were further isolated by their ethnicity: even other "Italians"

in the town (immigrants from mainland Italy; Rome, Naples, etc.) were slow to accept the "Sicilian

peasants".

The company intentionally grouped the miners'

living quarters by nationality. Poles and Slavic miners were on the West side of

town; Welsh, Irish and German in the middle; some Sicilians were in Woodvale, about a mile

away; and Italians and Sicilians were housed on the East side of Robertsdale on Spring

Street and Wood Street. The Italian/Sicilian sections were often referred to as

"Africa" by others.

The bias against the Sicilians had

repercussions. Two young Sicilian boys, the Latone (Latona) brothers, were

continually taunted by a local bully, Perry Everhardt. The younger Latona brother

had the chore of carrying water to his home each day. One morning Everhardt

tripped him, spilling the water. The boy went into his house, got his father's

shotgun, and shot and killed Everhardt. There are conflicting reports as to whether

he was ever punished. Some say that shortly after the shooting, five families of

Sicilians were evicted from Woodvale and moved to the East side of Robertsdale.

The 1922 strike may have been the final reason

Gaetano and his family left Robertsdale, but their leaving was likely spurred by a

number of factors: reported "lawlessness" among the Sicilians; fights

and shootings over card games or wine sales; the influenza epidemic of 1918, which claimed

a number of Sicilian victims (possibly including Angela Alessi Coniglio); the

"petering out" and eventual closing of some mines in the mid-twenties; and the

"black lung" disease, which many workers were beginning to contract, after ten

years in the mines.

Today, there are few Italian families in

Robertsdale. The local Pennsylvania dialect has modified even their names to suit the

community. Ciampa becomes "Sy-ampa", Marcocci is reduced to "Marcoss", and Rossi to "Ross".

The only remnant that we found of the Serradifalco Sicilians was

Vincenzo (Jim) Territo

(known locally as 'Jimmy Treat'), one of a local family of barbers whose father Calogero immigrated from

Serradifalco in 1903. Calogero was the grandson of another Calogero

Territo, who was born in Serradifalco in about 1804. That earlier

Calogero married my "half-GGG-aunt Gaetana Marino.

Jim Territo's father

Calogero was an illiterate miner, but as Jim described

it, "Somehow, my father found the Land Office in Pittsburgh and managed to buy

four acres of ground that wasn't owned by the mine company."

That

Calogero

Territo became

a land owner and businessman, even opening a store to compete with the "company

store". In doing so, he managed to do something the other Sicilians were

unable to do: establish roots in the community. My research of

Serradifalco roots some time after we met 'Jimmy Treat' found that my GGGG-grandmother

Crocifissa Papia re-married after

my GGGG-grandfather Pietro Lattuca died, and she and her second

husband Leonardo Marino had a daughter who married a Territo, and

were ancestors of Jimmy Treat. So Jimmy is my 'half-third cousin,

twice removed'!

I don't know if the following conversation

actually took place, but I can just hear

Rosa saying to Gaetano: "Li

Americani ni dispiacianu pirchi simmu 'Taliani. Li 'Taliani ni dispacianu pirchi

dicianu ca nun simmu Italiani. A Pittistoni, unn ti piaceru pirchi a

lavuratu cu lu carbuni "leggia" anzi di carbuni "duru".

La mia suru si ni ji a Sicilia. Lu maritu di la mia amica havi lu pulmuni

niru". Ora, c'e 'nu scioperu, e li pazzi ca bruscianu li casi

nustri. 'Ammunini di 'stu pustu!" ['The Americans dislike us because we're

Italian. The Italians dislike us because they say we're not Italian. In

Pittston, they even disliked you because you were a "soft" coal miner, not a

"hard" coal miner. My sister has gone back to Sicily. My friend's husband

has the "black lung". Now, there's a strike, and the

crazy ones who burn our houses. Let's go from

this place!']

After the

turbulence of the early 1920s, the Coniglio family and most, if not all of the other

Serradifalchese, walked to the train depot and boarded a narrow-gage East Broad Top Railroad train to Mount Union, whence they took a standard-gage train to points

north and Buffalo. Why they chose Buffalo, and whether they left en masse or in

dribs and drabs, we don't know (yet). Gaetano's naturalization papers

include affidavits by two friends from Robertsdale, Salvatore Latona and

Salvatore Giordano, who stated that the Coniglio family left Robertsdale

"in early 1921". Felice

(Phil) was born in Robertsdale in December, 1920, and Carmela

(Millie) was born in

Buffalo

in May, 1923. |